11 – Research

Finding and Evaluating Research Sources

Suzan Last; Kalani Pattison; and Nicole Hagstrom-Schmidt

In this “information age,” so much information is readily available on the Internet. With so much at our fingertips, it is crucial to be able to critically search and sort this information in order to select credible sources that can provide reliable and useful data to support your ideas and convince your audience.

Popular Sources vs Academic Sources

From your previous academic writing courses, you are likely familiar with academic journals and how they differ from popular sources, as in magazines shown in Figure 11.1. Academic journals contain peer-reviewed articles written by scholars for other scholars, often presenting their original research, reviewing the original research of others, or performing a “meta-analysis” (an analysis of multiple studies that analyze a given topic). Peer reviewing is a lengthy vetting process where each article is evaluated by other experts in the field.

Popular sources, in contrast, are written for a more general audience or following. While these pieces may be well researched, they are usually only vetted by an editor or if the writer seeks out additional review. Popular sources tend to be more accessible to wider audiences. They also tend to showcase more visible biases based on their intended readership or viewership. If you would like to refresh your memory on this topic, consult your library or writing center for resources.[1] Figure 11. 1 [2] below illustrates a newsstand with a number of popular sources.

In contrast to these covers of popular sources, Figure 11.2 [3] illustrates the front page of a scholarly journal article. The differences in layout, design, and information included demonstrate some of the differences in the priorities of these two types of sources.

Scholarly articles published in academic journals are usually required sources in academic research essays; they are also an integral part of engineering projects and technical reports. Furthermore, many projects require a literature review, which collects, summarizes, and sometimes evaluates the work of researchers in the field whose work has been recognized as a valuable contribution to that field. Scholarly sources such as journal articles are usually cited as the major contributors, though other scholarly documents including books, conference proceedings, and major reports may also be incorporated into a literature review based on the discipline the writer is in.

Journal articles are not the only kind of research you will find useful. Since you are researching in a professional field and preparing for the workplace, there are many credible kinds of sources you will draw on in a professional context. Table 11.2 lists several types of sources you may find useful in researching your projects.

Table 11.2. Typical research sources for technical projects.

| Source Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Academic Journals, Conference Papers, Dissertations, etc. | Scholarly (peer-reviewed) academic sources publish primary research done by professional researchers and scholars in specialized fields, as well as reviews of that research by other specialists in the same field.

For example, the Journal of Computer and System Sciences publishes original research papers in computer science and related subjects in system science; International Journal of Robotics and Animation is one of the most highly ranked journals in the field. |

| Reference Works | Specialized encyclopedias, handbooks, and dictionaries can provide useful terminology and background information.

For example, the Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology is a widely recognized authoritative source. Do not cite Wikipedia or dictionary.com in a technical report. For general information, use accepted reference materials in your field. For dictionary definitions, use either a definition provided in a scholarly source or the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). |

| Books, Chapters in Books | Books written by specialists in a given field and containing a References section can be very helpful in providing in-depth context for your ideas.

When selecting books, look at the publisher. Publishers affiliated with a university tend to be more credible than popular presses. For example, Designing Engineers by Susan McCahan et al. has an excellent chapter on effective teamwork. |

| Trade Magazines and Popular Science Magazines | Reputable trade magazines contain articles relating to current issues and innovations, and therefore they can be very useful in determining the “state of the art” or what is “cutting edge” at the moment, or finding out what current issues or controversies are affecting the industry.

Examples include Computerworld, Wired, and Popular Mechanics. |

| Newspapers (Journalism) | Newspaper articles and media releases can offer a sense of what journalists and people in industry think the general public should know about a given topic.

Journalists report on current events and recent innovations; more in-depth “investigative journalism” explores a current issue in greater detail. Newspapers also contain editorial sections that provide personal opinions on these events and issues. Choose well-known, reputable newspapers such as The New York Times and The Washington Post. |

| Industry Websites (.com) | Commercial websites are generally intended to “sell,” so you have to select information carefully. Nevertheless, these websites can give you insights into a company’s “mission statement,” organization, strategic plan, current or planned projects, archived information, white papers, technical reports, product details, costs estimates, etc. |

| Organization Websites (.org) | A vast array of .org sites can be very helpful in supplying data and information. These are often, but not always, public service sites and are designed to share information with the public. Remember, organizations can also have clear biases and missions, so keep that context in mind when reviewing them. |

| Government Publications and Public Sector Websites (.gov/.edu) | Government departments often publish reports and other documents that can be very helpful in determining public policy, regulations, and guidelines that should be followed.

Statistics Canada,[4] for example, publishes a wide range of data. University web sites also offer a wide array of non-academic information, such as strategic plans, facilities information, etc. |

| Patents | You may have to distinguish your innovative idea from previously patented ideas. You can look these up and get detailed information on patented or patent-pending ideas. |

| Public Presentations | Public Consultation meetings and representatives from industry and government speak to various audiences about current issues and proposed projects. These can be live presentations or video presentations available on YouTube or as TED talks. |

| Other | Some other examples include radio programs, podcasts, social media, Patreon, etc. |

Searching for scholarly and credible sources available to you through an academic library is not quite as simple as conducting a search on a popular internet search engine. See Appendix: Search Strategies to learn more about keywords, different ways of narrowing or broadening a search, and other information that will help you use your library’s resources to their fullest potential.

Evaluating Sources

The importance of critically evaluating your sources for authority, relevance, timeliness, and credibility cannot be overstated. Anyone can put anything on the internet, and people with strong web and document design skills can make this information look very professional and credible—even if it isn’t. Since much research is currently done online and many sources are available electronically, developing your critical evaluation skills is crucial to finding valid, credible evidence to support and develop your ideas. Even clear classifications of types of sources are no guarantee of objectivity or credibility. Some books may be published by presses with specific political agendas, and some journals, which look academic/scholarly at first glance, actually don’t use a robust peer-review method and instead focus on profit. Don’t blindly trust sources without carefully considering the whole context, and don’t dismiss a valuable source because it is popular, crowdsourced, or from a non-profit blog.

Note

Research Tip: One of the best ways to make sure you establish the credibility of your information is to triangulate your research—that is, try to find similar conclusions based on various data and from multiple sources. Find several secondary source studies that draw the same overall conclusion from different data, and see if the general principles can be supported by your own observations or primary research. For instance, when you are trying to examine how a course is taught, you want to make sure that you speak with the students and the professor, not just one or the other. Getting the most important data from a number of different sources and different types of sources can both boost the credibility of your findings and help your ethos overall.

When evaluating research sources and presenting your own research, be careful to critically evaluate the authority, content, and purpose of the material, using questions in Table 11.3. When evaluating sources for use in a document, consider how the source will affect your own credibility or ethos.

Table 11.3. Evaluating authority, content, and purpose of information.

| Evaluating Authority, Content, and Purpose of Information | |

|---|---|

| Authority Researchers Authors Creators |

Authoritative Sources: written by experts for a specialized audience, published in peer-reviewed journals or by respected publishers, and containing well-supported, evidence-based arguments. Popular Sources: written for a general (or possibly niche) public audience, often in an informal or journalistic style, published in newspapers, magazines, and websites with a purpose of entertaining or promoting a product; evidence is often “soft” rather than hard. |

| Content | Methods

Data

|

| Purpose Intended Use and Intended Audience |

|

When evaluating sources, you will also want to consider how you plan to use the source and why. There are several reasons for why you would use a particular source. Perhaps it is a scientific study that supports your claim that emissions from certain types of vehicles are higher than those of others. Or maybe the writer uses particularly effective phrasing or an example that your readers will respond to. Or perhaps it is a graph that effectively shows trends from the past ten years. Source use, like any choice you make when producing a document, should be purposeful.

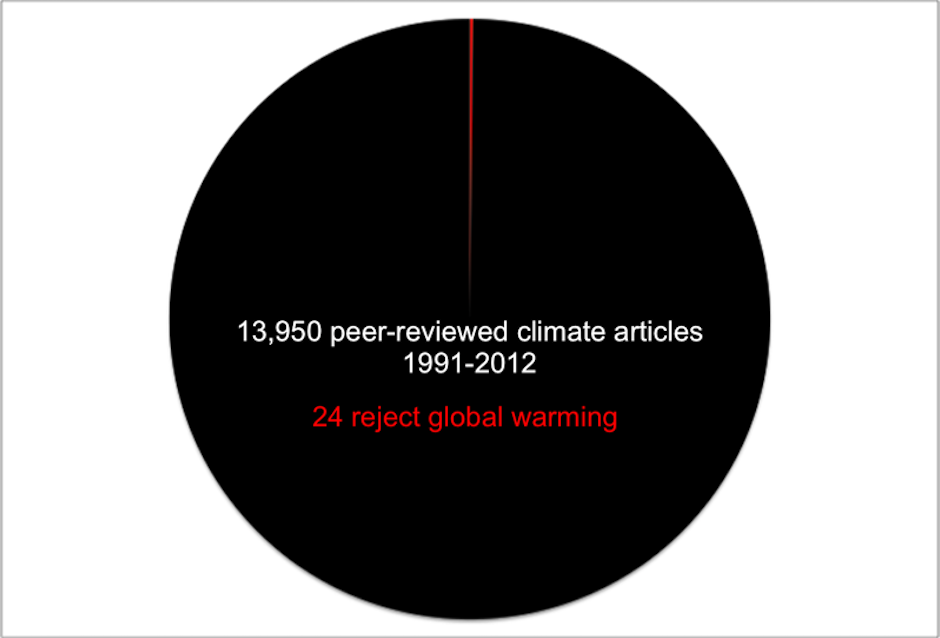

Part of using sources purposefully is interrogating your own reasons for using a source. Specifically, be aware of cherry picking and confirmation bias. Cherry picking is the use of inadequate or unrepresentative data that only supports your position and ignores substantial amounts of data that contradicts it. Comprehensive research addresses contradictory evidence from credible sources and uses all data to inform its conclusions. Confirmation bias refers to when you (unintentionally or otherwise) only consult sources that you know will support your idea. Given the pie chart in Figure 11.3, [5] if you only consulted articles that rejected global warming in a project related to that topic, you would be guilty of cherry picking and confirmation bias. (While we caution in Chapter 8: Graphics not to use pie charts with only two sections, the extreme contrast in this pie chart creates a valuable rhetorical effect.)

Finally, you will also want to consider if you are representing the collected data accurately. As a researcher, you are responsible for treating your sources ethically. Being ethical in this context means both attributing data to its sources and providing accurate context for that data. Occasionally, you may find a specific quotation or data point that seems to support one interpretation; however, once you read the source, you realize that the writer was describing an outlier or critiquing an incorrect point. Another common representation error is claiming that an author says something that they never actually say. In your text, you need to be clear regarding where your information is coming from and where your ideas diverge from those of the source. See Chapter 3 for more detailed discussion on bias.

This text was derived from

Last, Suzan, with contributors Candice Neveu and Monika Smith. Technical Writing Essentials: Introduction to Professional Communications in Technical Fields. Victoria, BC: University of Victoria, 2019. https://pressbooks.bccampus.ca/technicalwriting/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- Sarah LeMire, “ENGL 104 - Composition & Rhetoric (Spring 2022): Scholarly and Popular Sources,” Texas A&M University Libraries Research Guides, accessed February 4, 2022, https://tamu.libguides.com/c.php?g=715043&p=7697893. ↵

- Crookoo, “Magazine Magazines Journalism Press Newspaper,” Pixabay, accessed January 1, 2021, https://pixabay.com/photos/magazines-magazine-journalism-press-614897/. Licensed under a Pixabay License. ↵

- Mikael Laakso and Björk Bo-Christer, “Anatomy of Open Access Publishing: A Study of Longitudinal Development and Internal Structure,” BMC Medicine 10 (2012): 1-9, accessed February 4, 2022, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Anatomy_of_open_access_publishing_-_1741-7015-10-124.pdf. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License. ↵

- Government of Canada, “Statistics Canada,” Accessed August 11, 2020, http://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/start. ↵

- James Lawrence Powell, “Why Climate Deniers Have No Credibility—In One Pie Chart,” DeSmog Blog, accessed February 4, 2022, https://www.desmog.com/2012/11/15/why-climate-deniers-have-no-credibility-science-one-pie-chart)/. ↵

A comprehensive survey of scholarly literature (including books, peer-reviewed articles, and other documents based on the discipline) that evaluates and synthesizes key findings and developments related to a specific topic. Often included as part of report or study, but longer literature reviews may be published as articles on their own.

Use of inadequate or unrepresentative data that only supports one position and ignores substantial amounts of data that contradicts it.

Type of bias that occurs when someone seeks out and uses information that only confirms their current opinion.