7.6 Inverse Trigonometric Functions

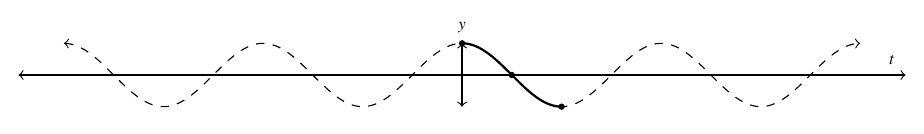

In this section we concern ourselves with finding inverses of the circular (trigonometric) functions.[1] Our immediate problem is that, owing to their periodic nature, none of the six circular functions are one-to-one. To remedy this, we restrict the domains of the circular functions in the same way we restricted the domain of the quadratic function in Example 5.1.3 in Section 5.1 to obtain a one-to-one function.

7.6.1 Inverses of Sine and Cosine

We start with ![]() and restrict our domain to

and restrict our domain to ![]() in order to keep the range as

in order to keep the range as ![]() as well as the properties of being smooth and continuous.

as well as the properties of being smooth and continuous.

Recall from Section 5.1 that the inverse of a function ![]() is typically denoted

is typically denoted ![]() . For this reason, some textbooks use the notation

. For this reason, some textbooks use the notation ![]() for the inverse of

for the inverse of ![]() . The obvious pitfall here is our convention of writing

. The obvious pitfall here is our convention of writing ![]() as

as ![]() ,

, ![]() as

as ![]() and so on. It is far too easy to confuse

and so on. It is far too easy to confuse ![]() with

with ![]() so we will not use this notation in our text.[2]

so we will not use this notation in our text.[2]

Instead, we use the notation ![]() , read `arc-sine of

, read `arc-sine of ![]() ‘. We’ll explain the `arc’ in `arcsine’ shortly. For now, we graph

‘. We’ll explain the `arc’ in `arcsine’ shortly. For now, we graph ![]() and

and ![]() , where we obtain the latter from the former by reflecting it across the line

, where we obtain the latter from the former by reflecting it across the line ![]() , in accordance with Theorem 5.1.

, in accordance with Theorem 5.1.

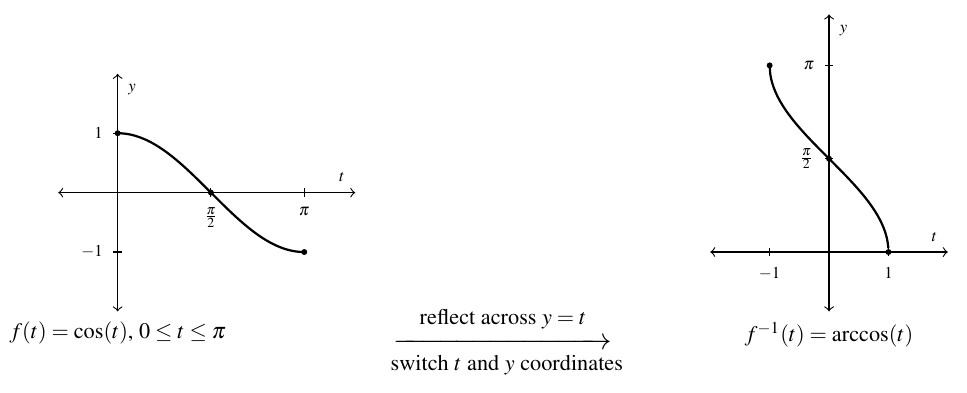

Next, we consider ![]() . Here, we select the interval

. Here, we select the interval ![]() for our restriction.

for our restriction.

Reflecting the across the line ![]() produces the graph

produces the graph ![]() .

.

We list some important facts about the arcsine and arccosine functions in the following theorem.[3] Everything in Theorem 7.15 is a direct consequence of Theorem 5.1 as applied to the (restricted) sine and cosine functions, and as such, its proof is left to the reader.

Theorem 7.15 Properties of the Arcsine and Arccosine Functions

- Properties of

- Domain:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com [-1,1]](https://odp.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-01968fac04e5065aa6fb740566b7905b_l3.png)

- Range:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \left[ -\frac{\pi}{2}, \frac{\pi}{2}\right]](https://odp.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-490a31c092ffaf66d88ed886f71746b1_l3.png)

if and only if

if and only if  and

and

provided

provided

provided

provided

is odd

is odd

- Domain:

- Properties of

- Domain:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com [-1,1]](https://odp.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-01968fac04e5065aa6fb740566b7905b_l3.png)

- Range:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com [0,\pi]](https://odp.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-bb159b8a07cfa44bd834f06db49a3640_l3.png)

if and only if

if and only if  and

and

provided

provided

provided

provided

- Domain:

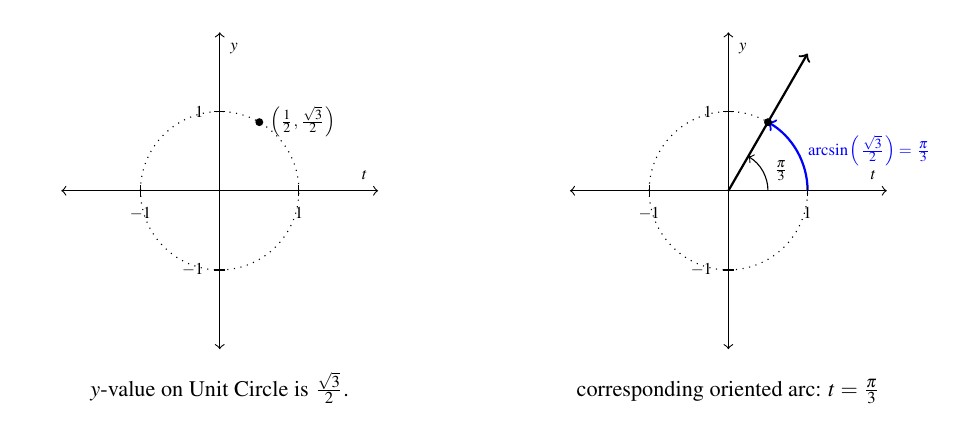

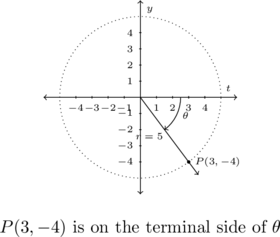

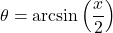

Before moving to an example, we take a moment to understand the `arc’ in `arcsine.’ Consider the figure below which illustrates the specific case of ![]() .

.

By definition, the real number ![]() satisfies

satisfies ![]() with

with ![]() . In other words, we are looking for angle measuring

. In other words, we are looking for angle measuring ![]() radians between

radians between ![]() and

and ![]() with a sine of

with a sine of ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() .

.

In terms of oriented arcs[4], if we start at ![]() and travel along the Unit Circle in the positive (counterclockwise) direction for

and travel along the Unit Circle in the positive (counterclockwise) direction for ![]() units, we will arrive at the point whose

units, we will arrive at the point whose ![]() -coordinate is

-coordinate is ![]() . Hence, the real number

. Hence, the real number ![]() also corresponds to `arc’ corresponding to the `sine’ that is

also corresponds to `arc’ corresponding to the `sine’ that is ![]() .

.

In general, the function ![]() takes a real number input

takes a real number input ![]() , associates it with the angle

, associates it with the angle ![]() radians, and returns the value

radians, and returns the value ![]() . The value

. The value ![]() is the

is the ![]() -coordinate of the terminal point on the Unit Circle of an oriented arc of length

-coordinate of the terminal point on the Unit Circle of an oriented arc of length ![]() whose initial point is

whose initial point is ![]() .

.

Hence, we may view the inputs to ![]() as oriented arcs and the outputs as

as oriented arcs and the outputs as ![]() -coordinates on the Unit Circle. Therefore, the function

-coordinates on the Unit Circle. Therefore, the function ![]() reverses this process and takes

reverses this process and takes ![]() -coordinates on the Unit Circle and return oriented arcs, hence the `arc’ in arcsine.

-coordinates on the Unit Circle and return oriented arcs, hence the `arc’ in arcsine.

Example 7.6.1

Example 7.6.1.1a

Determine the exact values of the following.

![]()

Solution:

The best way to approach these problems is to remember that ![]() and

and ![]() are real numbers which correspond to the radian measure of angles that fall within a certain prescribed range.

are real numbers which correspond to the radian measure of angles that fall within a certain prescribed range.

Determine the exact value of ![]() .

.

To find ![]() , we need the angle measuring

, we need the angle measuring ![]() radians which lies between

radians which lies between ![]() and

and ![]() with

with ![]() .

.

Hence, ![]() .

.

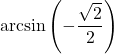

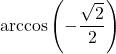

Example 7.6.1.1b

Determine the exact values of the following.

![]()

Solution:

The best way to approach these problems is to remember that ![]() and

and ![]() are real numbers which correspond to the radian measure of angles that fall within a certain prescribed range.

are real numbers which correspond to the radian measure of angles that fall within a certain prescribed range.

Determine the exact value of ![]() .

.

To find ![]() , we are looking for the angle measuring

, we are looking for the angle measuring ![]() radians which lies between

radians which lies between ![]() and

and ![]() that has

that has ![]() .

.

Our answer is ![]() .

.

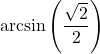

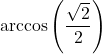

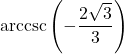

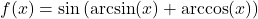

Example 7.6.1.1c

Determine the exact values of the following.

![]()

Solution:

The best way to approach these problems is to remember that ![]() and

and ![]() are real numbers which correspond to the radian measure of angles that fall within a certain prescribed range.

are real numbers which correspond to the radian measure of angles that fall within a certain prescribed range.

Determine the exact value of ![]() .

.

For ![]() , we are looking for an angle measuring

, we are looking for an angle measuring ![]() radians which lies between

radians which lies between ![]() and

and ![]() with

with ![]()

Hence, ![]() .

.

Alternatively, we could use the fact that the arcsine function is odd, so ![]() .

.

We find ![]() , so

, so ![]() .

.

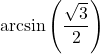

Example 7.6.1.1d

Determine the exact values of the following.

![]()

Solution:

The best way to approach these problems is to remember that ![]() and

and ![]() are real numbers which correspond to the radian measure of angles that fall within a certain prescribed range.

are real numbers which correspond to the radian measure of angles that fall within a certain prescribed range.

Determine the exact value of ![]() .

.

For ![]() , we need the angle measuring

, we need the angle measuring ![]() radians which lies between

radians which lies between ![]() and

and ![]() with

with ![]() .

.

Hence, ![]() .

.

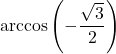

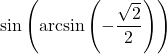

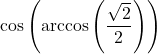

Example 7.6.1.1e

Determine the exact values of the following.

![]()

Solution:

The best way to approach these problems is to remember that ![]() and

and ![]() are real numbers which correspond to the radian measure of angles that fall within a certain prescribed range.

are real numbers which correspond to the radian measure of angles that fall within a certain prescribed range.

Determine the exact value of ![]() .

.

As ![]() , we could simply invoke Theorem 7.15 to get

, we could simply invoke Theorem 7.15 to get ![]() .

.

However, in order to make sure we understand why this is the case, we choose to work the example through using the definition of arccosine.

Working from the inside out, ![]() .

.

To find ![]() , we need an angle measuring

, we need an angle measuring ![]() radians which lies between

radians which lies between ![]() and

and ![]() that has

that has ![]() .

.

We get ![]() , so that

, so that ![]() .

.

Example 7.6.1.1f

Determine the exact values of the following.

![]()

Solution:

The best way to approach these problems is to remember that ![]() and

and ![]() are real numbers which correspond to the radian measure of angles that fall within a certain prescribed range.

are real numbers which correspond to the radian measure of angles that fall within a certain prescribed range.

Determine the exact value of ![]() .

.

![]() does not fall between

does not fall between ![]() and

and ![]() , therefore Theorem 7.15 does not apply. We are forced to work through from the inside out starting with

, therefore Theorem 7.15 does not apply. We are forced to work through from the inside out starting with ![]() . From the previous problem, we know

. From the previous problem, we know ![]() .

.

Hence, ![]() .

.

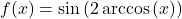

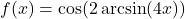

Example 7.6.1.1g

Determine the exact values of the following.

![]()

Solution:

The best way to approach these problems is to remember that ![]() and

and ![]() are real numbers which correspond to the radian measure of angles that fall within a certain prescribed range.

are real numbers which correspond to the radian measure of angles that fall within a certain prescribed range.

Determine the exact value of ![]() .

.

One way to simplify ![]() is to use Theorem 7.15 directly.

is to use Theorem 7.15 directly.

Because ![]() is between

is between ![]() and

and ![]() , we have that

, we have that ![]() and we are done.

and we are done.

However, as before, to really understand why this cancellation occurs, we let ![]() . By definition,

. By definition, ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() , and we are finished in (nearly) the same amount of time.

, and we are finished in (nearly) the same amount of time.

Example 7.6.1.1h

Determine the exact values of the following.

![]()

Solution:

The best way to approach these problems is to remember that ![]() and

and ![]() are real numbers which correspond to the radian measure of angles that fall within a certain prescribed range.

are real numbers which correspond to the radian measure of angles that fall within a certain prescribed range.

Determine the exact value of ![]() .

.

As in the previous example, we let ![]() so that

so that ![]() for some angle measuring

for some angle measuring ![]() radians between

radians between ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

For ![]() , we can narrow this down a bit and conclude that

, we can narrow this down a bit and conclude that ![]() , so that

, so that ![]() corresponds to an angle in Quadrant II.

corresponds to an angle in Quadrant II.

In terms of ![]() , then, we need to find

, then, we need to find ![]() , and because we know

, and because we know ![]() , the fastest route is using the Pythagorean Identity,

, the fastest route is using the Pythagorean Identity, ![]() or

or ![]() .[5]

.[5]

We get ![]() .

. ![]() corresponds to a Quadrant II angle, thus we choose the positive root,

corresponds to a Quadrant II angle, thus we choose the positive root, ![]() , so

, so ![]() .

.

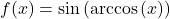

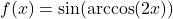

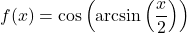

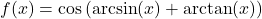

Example 7.6.1.2

Rewrite the composite function ![]() as algebraic functions of

as algebraic functions of ![]() and state the domain.

and state the domain.

Solution:

The best way to approach these problems is to remember that ![]() and

and ![]() are real numbers which correspond to the radian measure of angles that fall within a certain prescribed range.

are real numbers which correspond to the radian measure of angles that fall within a certain prescribed range.

Rewrite ![]() as an algebraic function of

as an algebraic function of ![]() and state the domain.

and state the domain.

We begin this problem in the same manner we began the previous two problems. We let ![]() , so our goal is to find a way to express

, so our goal is to find a way to express ![]() in terms of

in terms of ![]() .

.

By letting ![]() , we know

, we know ![]() where

where ![]() . One approach[6] to finding

. One approach[6] to finding ![]() is to use the quotient identity

is to use the quotient identity ![]() . As we know

. As we know ![]() , we just need to find

, we just need to find ![]() .

.

Using the Pythagorean Identity, ![]() , we get

, we get ![]() so that

so that ![]() . Given

. Given ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Thus, ![]() , so

, so ![]() .

.

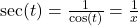

To determine the domain, we harken back to Section 1.5.2. The function ![]() can be thought of as a two step process: first, take the arccosine of a number, and second, take the tangent of whatever comes out of the arccosine.

can be thought of as a two step process: first, take the arccosine of a number, and second, take the tangent of whatever comes out of the arccosine.

The domain of ![]() is

is ![]() , so the domain of

, so the domain of ![]() will be some subset of

will be some subset of ![]() . The range of

. The range of ![]() is

is ![]() , and of these values, only

, and of these values, only ![]() will cause a problem for the tangent function. As

will cause a problem for the tangent function. As ![]() happens when

happens when ![]() , we exclude

, we exclude ![]() from our domain. Hence, the domain of

from our domain. Hence, the domain of ![]() is

is ![]() .

.

Note that in this particular case, we could have obtained the correct domain of ![]() using its algebraic description:

using its algebraic description: ![]() . This is not always true, however, as we’ll see soon.

. This is not always true, however, as we’ll see soon.

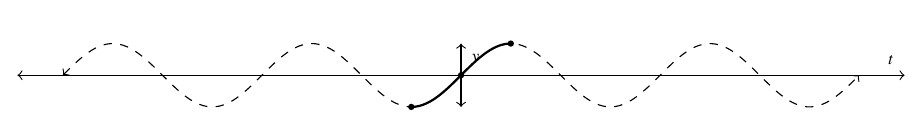

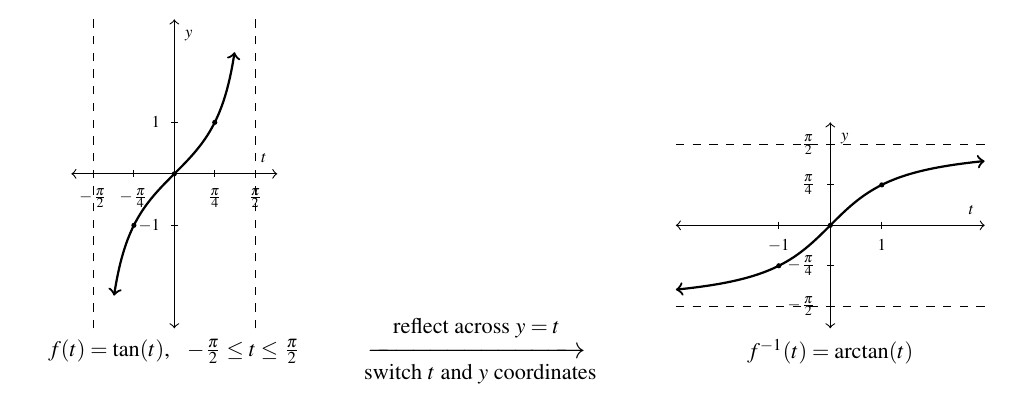

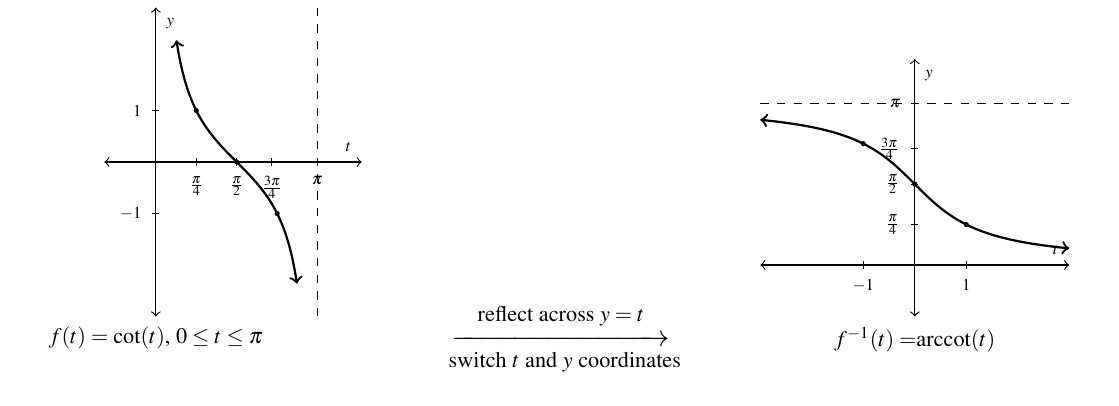

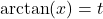

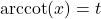

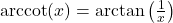

7.6.2 Inverses of Tangent and Cotangent

The next pair of functions we wish to discuss are the inverses of tangent and cotangent. First, we restrict ![]() to its fundamental cycle on

to its fundamental cycle on ![]() to obtain the arctangent function,

to obtain the arctangent function, ![]() . Among other things, note that the vertical asymptotes

. Among other things, note that the vertical asymptotes ![]() and

and ![]() of the graph of

of the graph of ![]() become the horizontal asymptotes

become the horizontal asymptotes ![]() and

and ![]() of the graph of

of the graph of ![]() .

.

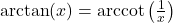

Next, we restrict ![]() to its fundamental cycle on

to its fundamental cycle on ![]() to obtain

to obtain ![]() , the arccotangent function. Once again, the vertical asymptotes

, the arccotangent function. Once again, the vertical asymptotes ![]() and

and ![]() of the graph of

of the graph of ![]() become the horizontal asymptotes

become the horizontal asymptotes ![]() and

and ![]() of the graph of

of the graph of ![]() .

.

Below we summarize the important properties of the arctangent and arccotangent functions.

Theorem 7.16 Properties of the Arctangent and Arccotangent Functions

- Properties of

- Domain:

- Range:

- as

,

,  ; as

; as  ,

,

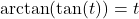

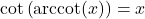

if and only if

if and only if  and

and

for

for

for all real numbers

for all real numbers

provided

provided

is odd

is odd

- Domain:

- Properties of

- Domain:

- Range:

- as

,

,  ; as

; as  ,

,

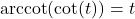

if and only if

if and only if  and

and

for

for

for all real numbers

for all real numbers

provided

provided

- Domain:

The properties listed in Theorem 7.16 are consequences of the definitions of the arctangent and arccotangent functions along with Theorem 5.1, and its proof is left to the reader.

Example 7.6.2

Example 7.6.2.1a

Determine the exact values of the following.

![]()

Solution:

Determine the exact value of ![]() .

.

To find ![]() , we need the angle measuring

, we need the angle measuring ![]() radians which lies between

radians which lies between ![]() and

and ![]() with

with ![]() .

.

We find ![]() .

.

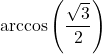

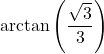

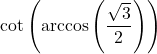

Example 7.6.2.1b

Determine the exact values of the following.

![]()

Solution:

Determine the exact value of ![]() .

.

To find ![]() , we need the angle measuring

, we need the angle measuring ![]() radians which lies between

radians which lies between ![]() and

and ![]() with

with ![]() .

.

Hence, ![]() .

.

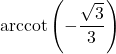

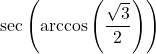

Example 7.6.2.1c

Determine the exact values of the following.

![]()

Solution:

Determine the exact value of ![]() .

.

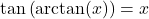

We can apply Theorem 7.16 directly and obtain ![]() . However, working it through provides us with yet another opportunity to understand why this is the case.

. However, working it through provides us with yet another opportunity to understand why this is the case.

Letting ![]() , by definition,

, by definition, ![]() .

.

Hence, ![]() .

.

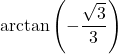

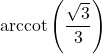

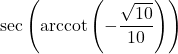

Example 7.6.2.1d

Determine the exact values of the following.

![]()

Solution:

Determine the exact value of ![]() .

.

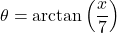

We start simplifying ![]() by letting

by letting ![]() . By definition,

. By definition, ![]() for some angle measuring

for some angle measuring ![]() radians which lies between

radians which lies between ![]() and

and ![]() . As

. As ![]() , we know, in fact,

, we know, in fact, ![]() corresponds to a Quadrant IV angle.

corresponds to a Quadrant IV angle.

We are given ![]() but wish to know

but wish to know ![]() . There is no direct identity to marry the two, so we make a quick sketch of the situation below. Because

. There is no direct identity to marry the two, so we make a quick sketch of the situation below. Because ![]() , we take

, we take ![]() as a point on the terminal side of

as a point on the terminal side of ![]() radians.

radians.

We find ![]() , so

, so ![]() .

.

Hence, ![]() .

.

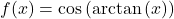

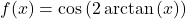

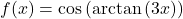

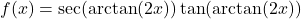

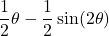

Example 7.6.2.2a

Rewrite each of the following composite functions as algebraic functions of ![]() and state the domain.

and state the domain.

![]()

Solution:

Rewrite ![]() as an algebraic function of

as an algebraic function of ![]() and state the domain.

and state the domain.

We proceed as above and let ![]() . We have

. We have ![]() where

where ![]() . Our goal is to express

. Our goal is to express ![]() in terms of

in terms of ![]() .

.

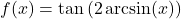

From Theorem 8.9, we will learn ![]() .

.

Hence ![]() .

.

To find the domain, we once again think of ![]() as a sequence of steps and work from the inside out.

as a sequence of steps and work from the inside out.

The first step is to find the arctangent of a real number. The domain of ![]() is all real numbers, so we have no restrictions here and we get out all values

is all real numbers, so we have no restrictions here and we get out all values ![]() .

.

The next step is to multiply ![]() by

by ![]() . There are no restrictions here, either. The range of

. There are no restrictions here, either. The range of ![]() is

is ![]() , thus the range of

, thus the range of ![]() is

is ![]() .

.

The last step is to take the tangent of ![]() . As we are taking the tangent of values in the interval

. As we are taking the tangent of values in the interval ![]() , we will run into trouble if

, we will run into trouble if ![]() , that is, if

, that is, if ![]() . This happens exactly when

. This happens exactly when ![]() , so we must exclude

, so we must exclude ![]() from the domain of

from the domain of ![]() .

.

Hence, the domain of ![]() is

is ![]() . In this example, we could have obtained the correct answer by looking at the algebraic equivalence,

. In this example, we could have obtained the correct answer by looking at the algebraic equivalence, ![]() .

.

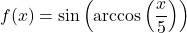

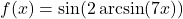

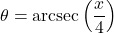

Example 7.6.2.2b

Rewrite each of the following composite functions as algebraic functions of ![]() and state the domain.

and state the domain.

![]()

Solution:

Rewrite ![]() as an algebraic function of

as an algebraic function of ![]() and state the domain.

and state the domain.

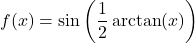

To get started, we let ![]() so that

so that ![]() where

where ![]() . In terms of

. In terms of ![]() ,

, ![]() , and our goal is to express the latter in terms of

, and our goal is to express the latter in terms of ![]() .

.

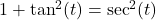

One way to proceed is to rewrite the identity ![]() as

as ![]() and use the fact that

and use the fact that ![]() to find

to find ![]() in terms of

in terms of ![]() . This isn’t as hopeless as it might seem, because the Pythagorean Identity

. This isn’t as hopeless as it might seem, because the Pythagorean Identity ![]() relates cotangent to cosecant, and

relates cotangent to cosecant, and ![]() .

.

Following this strategy, we get ![]() so

so ![]() . Due to the fact that

. Due to the fact that ![]() is between

is between ![]() and

and ![]() ,

, ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() , so

, so ![]() .

.

We find ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() .

.

Viewing ![]() as a sequence of steps, we see we first double the input

as a sequence of steps, we see we first double the input ![]() , then take the arccotangent, and, finally, take the cosine. Each of these processes are valid for all real numbers, so the domain of

, then take the arccotangent, and, finally, take the cosine. Each of these processes are valid for all real numbers, so the domain of ![]() is

is ![]() .

.

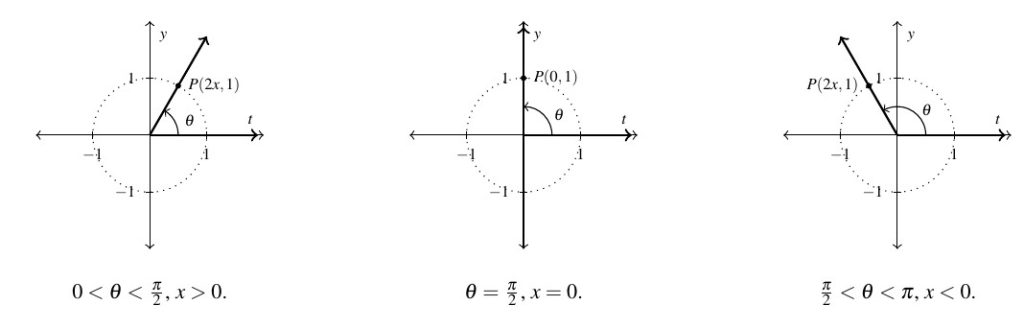

The reader may well wonder if there isn’t a more direct way to handle Example 7.6.2 number 2b. Indeed, we can take some inspiration from Section 7.4 and imagine an angle ![]() measuring

measuring ![]() radians so that

radians so that ![]() where

where ![]() .

.

Thinking of ![]() as a ratio of coordinates on a circle, we may rewrite

as a ratio of coordinates on a circle, we may rewrite ![]() and we would like to identify a point

and we would like to identify a point ![]() on the terminal side of

on the terminal side of ![]() .

.

We need to be careful here. Given ![]() ,

, ![]() , so as

, so as ![]() ranges between

ranges between ![]() and

and ![]() ,

, ![]() can take on positive, negative or

can take on positive, negative or ![]() values. We need to argue that the point

values. We need to argue that the point ![]() lies in the quadrant we expect (as depicted below) in all cases before we delve too far into our analysis.

lies in the quadrant we expect (as depicted below) in all cases before we delve too far into our analysis.

If ![]() , then

, then ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() so the point

so the point ![]() is in Quadrant I, as required. If

is in Quadrant I, as required. If ![]() , then

, then ![]() , and our point

, and our point ![]() , as required. If

, as required. If ![]() , then

, then ![]() . Hence,

. Hence, ![]() , so

, so ![]() is in Quadrant II, as required.

is in Quadrant II, as required.

Hence, in all three cases, our formula for the point ![]() determines a point in the same quadrant as the terminal side of

determines a point in the same quadrant as the terminal side of ![]() , as illustrated above.

, as illustrated above.

This allows us to use Theorem 7.10 from Section 7.4. We find ![]() , and hence,

, and hence, ![]() , which agrees with our answer from Example 7.6.2.

, which agrees with our answer from Example 7.6.2.

It shouldn’t surprise the reader that there are some cases where the approach outlined above doesn’t go as smoothly (as we’ll see in the discussion following Example 7.6.3.)

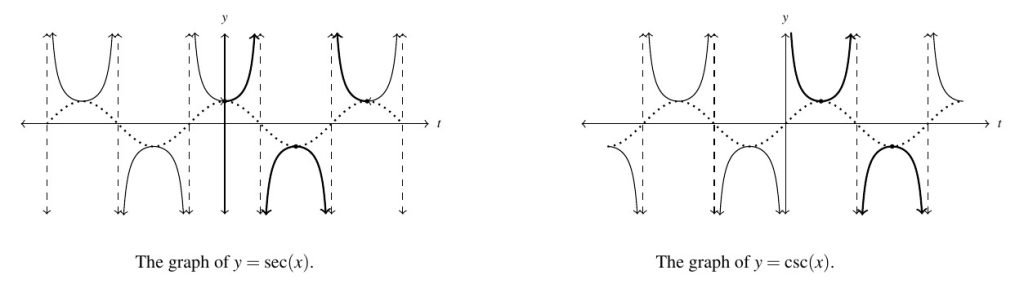

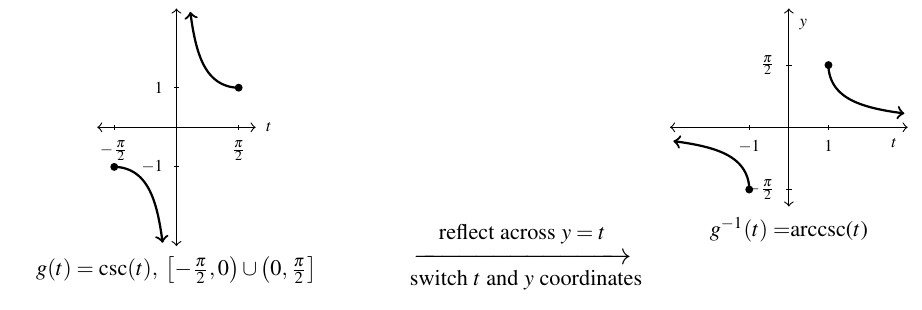

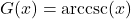

The last two functions to invert are secant and cosecant. A portion of each of their graphs, which were first discussed in Subsection 7.5.1, are given below with the fundamental cycles highlighted.

It is clear from the graph of secant that we cannot find one single continuous piece of its graph which covers its entire range of ![]() and restricts the domain of the function so that it is one-to-one. The same is true for cosecant.

and restricts the domain of the function so that it is one-to-one. The same is true for cosecant.

Thus in order to define the arcsecant and arccosecant functions, we must settle for a piecewise approach wherein we choose one piece to cover the top of the range, namely ![]() , and another piece to cover the bottom, namely

, and another piece to cover the bottom, namely ![]() .

.

There are two generally accepted ways to make these choices which restrict the domains of these functions so that they are one-to-one. One approach simplifies the Trigonometry associated with the inverse functions, but complicates the Calculus; the other makes the Calculus easier, but the Trigonometry less so. We choose to focus on the Trigonometric approach.

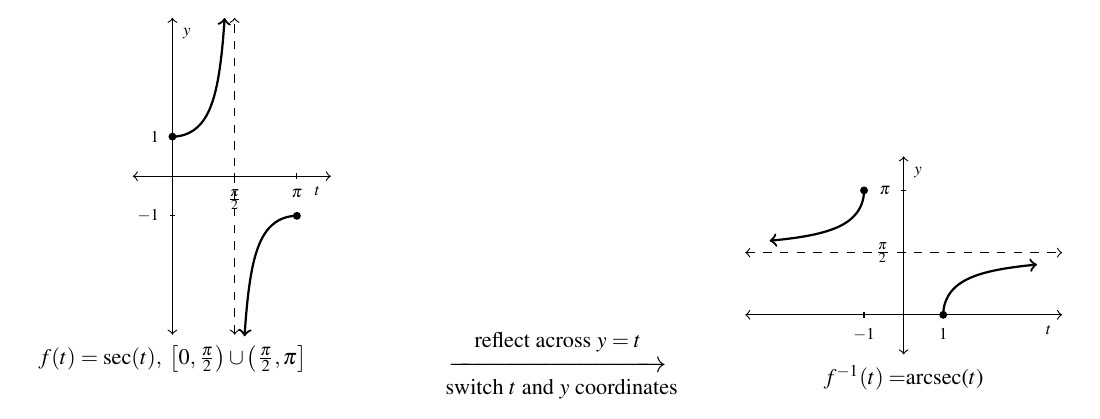

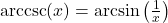

7.6.3 Inverses of Secant and Cosecant

In this subsection, we restrict the secant and cosecant functions to coincide with the restrictions on cosine and sine, respectively. For ![]() , we restrict the domain to

, we restrict the domain to ![]()

and we restrict ![]() to

to ![]() .

.

Note that for both arcsecant and arccosecant, the domain is ![]() . Taking a page from Section 0.6.2, we can rewrite this as

. Taking a page from Section 0.6.2, we can rewrite this as ![]() . (This is often done in Calculus textbooks, so we include it here for completeness.)

. (This is often done in Calculus textbooks, so we include it here for completeness.)

Using these definitions along with Theorem 5.1, we get the following properties of the arcsecant and arccosecant functions.

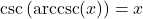

Theorem 7.17 Properties of the Arcsecant and Arccosecant Functions

- Properties of

- Domain:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \left\{ x \, | \, |x| \geq 1 \right\} = (-\infty, -1] \cup [1,\infty)](https://odp.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-8366b599424cb65e425e841144373d60_l3.png)

- Range:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \left[0, \frac{\pi}{2} \right) \cup \left(\frac{\pi}{2}, \pi\right]](https://odp.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-73d501b0452cfa6e6d55c0032a7ff3b0_l3.png)

- as

,

,  ; as

; as  ,

,

if and only if

if and only if  and

and  or

or

provided

provided

provided

provided

provided

provided  or

or

- Domain:

- Properties of

- Domain:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \left\{ x \, | \, |x| \geq 1 \right\} = (-\infty, -1] \cup [1,\infty)](https://odp.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-8366b599424cb65e425e841144373d60_l3.png)

- Range:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \left[-\frac{\pi}{2}, 0 \right) \cup \left(0, \frac{\pi}{2} \right]](https://odp.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-f7110236bbfc97df023599367d258fe4_l3.png)

- as

,

,  ; as

; as  ,

,

if and only if

if and only if  and

and  or

or

provided

provided

provided

provided

provided

provided  or

or

is odd

is odd

- Domain:

The reason the ranges here are called `Trigonometry Friendly’ is specifically because of two properties listed in Theorem 7.17: ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Note: We may also “adjust” the restriction of

![]() to

to ![]() and

and ![]() to

to ![]() to develop `Calculus Friendly’ ranges of

to develop `Calculus Friendly’ ranges of ![]() for

for ![]() and

and ![]() for

for ![]() . At this time it is difficult to explain why these choices for the ranges of arcsecant and arccosecant are `Calculus Friendly.’

. At this time it is difficult to explain why these choices for the ranges of arcsecant and arccosecant are `Calculus Friendly.’

These formulas essentially allow us to always convert arcsecants and arccosecants back to arccosines and arcsines, respectively. We see this play out in our next example.

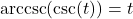

Example 7.6.3

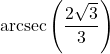

Example 7.6.3.1a

Determine the exact values of the following.

![]()

Solution:

Determine the exact value of ![]() .

.

Using Theorem 7.17, we have ![]() .

.

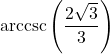

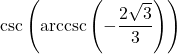

Example 7.6.3.1b

Determine the exact values of the following.

![]()

Solution:

Determine the exact value of ![]() .

.

Once again, Theorem 7.17 comes to our aid giving ![]() .

.

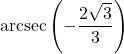

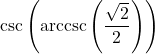

Example 7.6.3.1c

Determine the exact values of the following.

![]()

Solution:

Determine the exact value of ![]() .

.

![]() doesn’t fall between

doesn’t fall between ![]() and

and ![]() or

or ![]() and

and ![]() , thus we cannot use the inverse property stated in Theorem 7.17. Hence, we work from the `inside out.’

, thus we cannot use the inverse property stated in Theorem 7.17. Hence, we work from the `inside out.’

We get: ![]() .

.

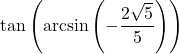

Example 7.6.3.1d

Determine the exact values of the following.

![]()

Solution:

Determine the exact value of ![]() .

.

We begin simplifying ![]() by letting

by letting ![]() . Then,

. Then, ![]() . For

. For ![]() ,

, ![]() lies in the interval

lies in the interval ![]() , so

, so ![]() corresponds to a Quadrant IV angle.

corresponds to a Quadrant IV angle.

To find ![]() , we use the Pythagorean Identity:

, we use the Pythagorean Identity: ![]() . We get

. We get ![]() , or

, or ![]() .

.

As ![]() corresponds to a Quadrant IV angle,

corresponds to a Quadrant IV angle, ![]() .

.

Hence, ![]() .

.

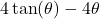

Example 7.6.3.2a

Rewrite each of the following composite functions as algebraic functions of ![]() and state the domain.

and state the domain.

![]()

Solution:

Rewrite ![]() as an algebraic function of

as an algebraic function of ![]() and state the domain.

and state the domain.

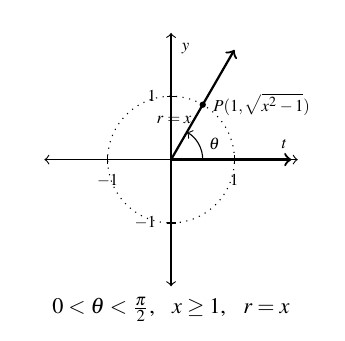

Proceeding as above, we let ![]() . Then,

. Then, ![]() for

for ![]() in

in ![]() . We seek a formula for

. We seek a formula for ![]() in terms of

in terms of ![]() .

.

To relate ![]() to

to ![]() , we use the Pythagorean Identity:

, we use the Pythagorean Identity: ![]() . Substituting

. Substituting ![]() , we get

, we get ![]() , so

, so ![]()

If ![]() belongs to

belongs to ![]() then

then ![]() . On the the other hand, if

. On the the other hand, if ![]() belongs to

belongs to ![]() then

then ![]() . As a result, we get a piecewise defined function for

. As a result, we get a piecewise defined function for ![]() :

:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \tan(t) = \left\{ \begin{array}{rr} \sqrt{x^2-1}, & \text{if $0 \leq t < \frac{\pi}{2}$} \\ [5pt] -\sqrt{x^2-1}, & \text{if $\frac{\pi}{2} < t \leq \pi$} \end{array}\right. \]](https://odp.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-cbdbd731ec42f1f2ff1e931ef794cc94_l3.png)

Now we need to determine what these conditions on ![]() mean for

mean for ![]() . For

. For ![]() , when

, when ![]() ,

, ![]() , and when

, and when ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

,

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[f(x) = \tan(\text{arcsec}(x)) = \left\{ \begin{array}{rr} \sqrt{x^2-1}, & \text{if $x \geq 1$} \\[5pt] -\sqrt{x^2-1}, & \text{if $x \leq -1$} \end{array}\right. \]](https://odp.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-790b6b3b24b03b32a523e513e2a11247_l3.png)

To find the domain of ![]() , we consider

, we consider ![]() as a two step process. First, we have the arcsecant function, whose domain is

as a two step process. First, we have the arcsecant function, whose domain is ![]()

The range of ![]() is

is ![]() , so taking the tangent of any output from

, so taking the tangent of any output from ![]() is defined. Hence, the domain of

is defined. Hence, the domain of ![]() is

is ![]()

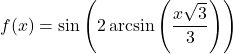

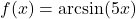

Example 7.6.3.2b

Rewrite each of the following composite functions as algebraic functions of ![]() and state the domain.

and state the domain.

![]()

Solution:

Rewrite ![]() as an algebraic function of

as an algebraic function of ![]() and state the domain.

and state the domain.

Taking a cue from the previous problem, we start by letting ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() for

for ![]() in

in ![]() . Our goal is to rewrite

. Our goal is to rewrite ![]() in terms of

in terms of ![]() .

.

From ![]() , we get

, we get ![]() , so to find

, so to find ![]() , we can make use of the Pythagorean Identity:

, we can make use of the Pythagorean Identity: ![]() . Substituting

. Substituting ![]() gives

gives ![]() . Getting a common denominator and extracting square roots, we obtain:

. Getting a common denominator and extracting square roots, we obtain:

![]()

As ![]() belongs to

belongs to ![]() , we know

, we know ![]() , so we choose

, so we choose ![]() . (The absolute values here are necessary, because

. (The absolute values here are necessary, because ![]() could be negative.) Therefore,

could be negative.) Therefore,

![]()

To find the domain of ![]() , as usual, we think of

, as usual, we think of ![]() as a series of processes. First, we take the input,

as a series of processes. First, we take the input, ![]() , and multiply it by

, and multiply it by ![]() . This can be done to any real number, so we have no restrictions here.

. This can be done to any real number, so we have no restrictions here.

Next, we take the arccosecant of ![]() . Using interval notation, the domain of the arccosecant function is written as:

. Using interval notation, the domain of the arccosecant function is written as: ![]() . Hence to take the arccosecant of

. Hence to take the arccosecant of ![]() , the quantity

, the quantity ![]() must lie in one of these two intervals.[7] That is,

must lie in one of these two intervals.[7] That is, ![]() or

or ![]() , so

, so ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

The third and final process coded in ![]() is to take the cosine of

is to take the cosine of ![]() . As the cosine accepts any real number, we have no additional restrictions. Hence, the domain of

. As the cosine accepts any real number, we have no additional restrictions. Hence, the domain of ![]() is

is ![]() .

.

As promised in the discussion following Example 7.6.2, in which we used the methods from Section 7.4 to circumvent some onerous identity work, we take some time here to revisit number 2a to see what issues arise when we take a Section 7.4 approach here.

As above, we start rewriting ![]() by letting

by letting ![]() so that

so that ![]() where

where ![]() or

or ![]() . We let

. We let ![]() radians and wish to view

radians and wish to view ![]() as described in Theorem 7.10: the ratio of the radius of a circle,

as described in Theorem 7.10: the ratio of the radius of a circle, ![]() centered at the origin, divided by the abscissa[8] of a point on the terminal side of

centered at the origin, divided by the abscissa[8] of a point on the terminal side of ![]() which intersects said circle.

which intersects said circle.

If we make the usual identification ![]() , we see that if

, we see that if ![]() , then

, then ![]() , so it makes sense to identify the quantity

, so it makes sense to identify the quantity ![]() as the radius of the circle with

as the radius of the circle with ![]() as the abscissa of the point where the terminal side of

as the abscissa of the point where the terminal side of ![]() intersects said circle. To find the associated ordinate (

intersects said circle. To find the associated ordinate (![]() -coordinate), we have

-coordinate), we have ![]() so

so ![]() , where we have chosen the positive root as we are in Quadrant I. We sketch out this scenario below.

, where we have chosen the positive root as we are in Quadrant I. We sketch out this scenario below.

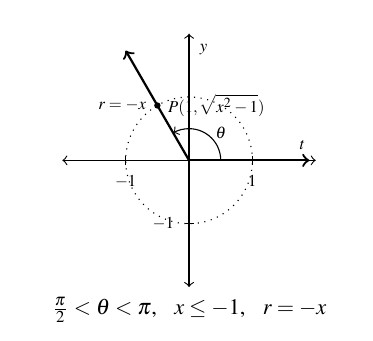

If, however, ![]() , then

, then ![]() , so we need to rewrite

, so we need to rewrite ![]() in order to keep the radius of the circle,

in order to keep the radius of the circle, ![]() and the abscissa,

and the abscissa, ![]() . From

. From ![]() , we still get

, we still get ![]() , as shown below.

, as shown below.

In the Quadrant I case, when ![]() , we get

, we get ![]() . In Quadrant II, when

. In Quadrant II, when ![]() , we obtain

, we obtain ![]() . Hence, we get the piecewise definition for

. Hence, we get the piecewise definition for ![]() as we did in number 2a above:

as we did in number 2a above: ![]() if

if ![]() and

and ![]() if

if ![]()

The moral of the story here is that you are free to choose whichever route you like to simplify expressions like those found in Example 7.6.3 number 2a. Whether you choose identities or a more geometric route, just be careful to keep in mind which quadrants are in play, which variables represent which quantities, and what signs (![]() ) each should have.

) each should have.

7.6.4 Section Exercises

In Exercises 1 – 40, compute the exact value.

In Exercises 41 – 48, assume that the range of arcsecant is ![]() and that the range of arccosecant is

and that the range of arccosecant is ![]() when finding the exact value. (See Section 7.6.3.)

when finding the exact value. (See Section 7.6.3.)

In Exercises 49 – 56, assume that the range of arcsecant is ![]() and that the range of arccosecant is

and that the range of arccosecant is ![]() when finding the exact value. (See Section 7.6.3.)

when finding the exact value. (See Section 7.6.3.)

In Exercises 57 – 86, determine the exact value or state that it is undefined.

In Exercises 87 – 106, determine the exact value or state that it is undefined.

In Exercises 107 – 118, assume that the range of arcsecant is ![]() and that the range of arccosecant is

and that the range of arccosecant is ![]() when finding the exact value. (See Section 7.6.3.)

when finding the exact value. (See Section 7.6.3.)

In Exercises 119 – 130, assume that the range of arcsecant is ![]() and that the range of arccosecant is

and that the range of arccosecant is ![]() when finding the exact value.

when finding the exact value.

In Exercises 131 – 154, compute the exact value or state that it is undefined.

In Exercises 155 – 164, determine the exact value or state that it is undefined.

In Exercises 165 – 184, rewrite each of the following composite functions as algebraic functions of ![]() and state the domain.

and state the domain.

- If

, find an expression for

, find an expression for  in terms of

in terms of  .

. - If

, find an expression for

, find an expression for  in terms of

in terms of  .

. - If

, find an expression for

, find an expression for  in terms of

in terms of  assuming

assuming

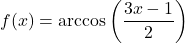

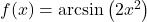

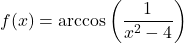

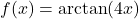

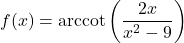

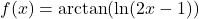

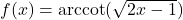

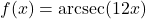

In Exercises 188 – 199, find the domain of the given function. Write your answers in interval notation.

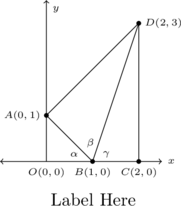

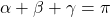

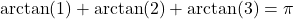

- Use the diagram below along with the accompanying questions to show:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\arctan(1) + \arctan(2) + \arctan(3) = \pi\]](https://odp.library.tamu.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-9fa279ba215b279b9266e9b71650f6bf_l3.png)

- Clearly

and

and  are right triangles because the line through

are right triangles because the line through  and

and  and the line through

and the line through  and

and  are perpendicular to the

are perpendicular to the  -axis. Use the distance formula to show that

-axis. Use the distance formula to show that  is also a right triangle (with

is also a right triangle (with  being the right angle) by showing that the sides of the triangle satisfy the Pythagorean Theorem.

being the right angle) by showing that the sides of the triangle satisfy the Pythagorean Theorem. - Use

to show that

to show that

- Use

to show that

to show that

- Use

to show that

to show that

- Use the fact that

,

,  and

and  all lie on the

all lie on the  -axis to conclude that

-axis to conclude that  . Thus

. Thus  .

.

- Clearly

Section 7.6 Exercise Answers can be found in the Appendix … Coming soon

- We have already discussed this concept in Section 7.2.1 as the `angle finder' in the context of acute angles in right triangles. ↵

- But be aware that many books do! As always, be sure to check the context! ↵

- We switch the input variable to the arcsine and arccosine functions to `

' to avoid confusion with the outputs we label `

' to avoid confusion with the outputs we label ` .' ↵

.' ↵ - See Section 7.1 if you need a review of how we associate real numbers with angles in radian measure. ↵

- The Pythagorean Identities are a direct result of the definition of the six trigonometric functions on a right triangle. We will prove these identities in this example in Section 8.1. See Theorem 8.3 ↵

- Alternatively, we could use the identity:

. As

. As  ,

,  . The reader is invited to work through this approach to see what, if any, difficulties arise. ↵

. The reader is invited to work through this approach to see what, if any, difficulties arise. ↵ - Alternatively, we can write the domain of

as

as  , so the domain of

, so the domain of  is

is  . ↵

. ↵ - We'll avoid the label `

-coordinate' here because as we'll see, the quantity

-coordinate' here because as we'll see, the quantity  in this problem is tied to the radius as opposed to the coordinates of points on the terminal side of

in this problem is tied to the radius as opposed to the coordinates of points on the terminal side of  . ↵

. ↵