VII. Researched Writing

7.5 Finding Supporting Information

Deborah Bernnard; Greg Bobish; Jenna Hecker; Irina Holden; Allison Hosier; Trudi Jacobson; Tor Loney; Daryl Bullis; Sarah LeMire; and Terri Pantuso

Harry and Emma Dennis have lived in Texas for 25 years. They work as teachers in the Fort Worth Independent School District. Lately, they have been closely following the debate about hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, in Texas and are concerned about their ability to influence the course of fracking in the future. Although they don’t own much land, they are worried about the possible adverse effects on drinking water, disruption to their environment, and the influx of people that fracking-related jobs will bring into their city. Though no new fracking permits are currently being issued, Emma Dennis is still concerned about existing practices. She is considering running for public office in her town to have a more powerful voice in the fracking debate. To receive the backing of her local political party, Emma needs to present some persuasive arguments against hydraulic fracking that are well thought out and scientifically sound. She needs to engage in substantial research on this issue so that she can present herself as an expert.

At this point, all that Emma really knows about fracking is what she has heard from neighbors and news shows. How will she proceed with her research? Emma’s intentions are commendable and she knows she will have to fill in the information gaps in her fracking-issue-knowledge before she can be taken seriously as a candidate for city office. Knowing that you don’t have sufficient information to solve an information need is one important aspect of information literacy. It enables you to obtain that missing information.

Different Information Formats and Their Characteristics

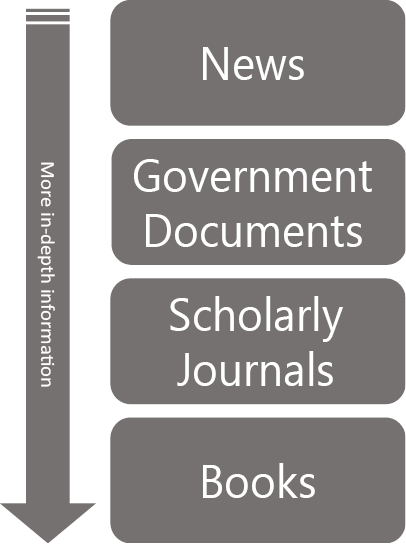

In addition to knowing that you are missing essential information, another component of information literacy is understanding that the information you seek may be available in different formats such as books, journal articles, government documents, blog postings, and news items. Each format has a unique value. Figure 7.5.1[1] below represents a common process of information dissemination. When an event happens, we usually hear about it from news sources—broadcast, web, and print. More in-depth exploration and analysis of the event often comes from government studies and scholarly journal articles. Deeper exploration, as well as an overview of much of the information available about the event, is often published in book format.

Emma realizes that she needs to obtain an overview of the whole fracking debate. She needs to determine how severe the consequences of fracking could be and what is actually involved in the fracking process. Where can she find such an overview and how can she trust that the overview is accurate and complete?

Emma believes that she can find this information online and uses Google to search the World Wide Web. She quickly finds that there is an overwhelming amount of online information about fracking. Her search has resulted in more than 11,000,000 sites. Emma knows that she doesn’t have time to look through all of these resources, and those that she does examine do not provide a comprehensive overview of the issues. She also notices that many of the sites are obviously advocating their own point of view.

A better first step for Emma to take is to identify a library that contains academic resources so that she will have access to more scholarly treatments of the subject. Emma can use the Texas A&M University Libraries’ Quick Search or Worldcat.org which will allow her to search numerous academic libraries at once.

Library Catalogs

A library catalog is a database that contains all of the items located in a library as well as all of the items to which the library has access. It allows you to search for items by title, author, subject, and keyword. A keyword is a word that is found anywhere within the record of an item in the catalog. A catalog record displays information that is pertinent to one item, which could be a book, a journal, a government document, or a video or audio recording.

If you search by subject in an academic library catalog you can take advantage of the controlled vocabulary created by the Library of Congress. Controlled vocabulary consists of terms or phrases that have been selected to describe a concept. For example, the Library of Congress has selected the phrase motion picture to represent films and movies. So, if you are looking for books about movies, you would enter the phrase motion picture into the search box. Controlled vocabulary is important because it helps pull together all of the items about one topic. In this example, you would not have to conduct individual searches for movies, then motion pictures, then film; you could just search once for motion pictures and retrieve all the items on movies and film. You can discover subject terms in item catalog records.

Many libraries provide catalog discovery interfaces that provide cues to help refine a search. This makes it easier to find items on specific topics. For example, if Emma enters the search terms hydraulic fracturing into a catalog with a discovery interface, the results page will include suggestions for refinements including several different aspects of the topic. Emma can click on any of these suggested refinements to focus her search.

Using this method, Emma finds several good resources on her topic. Now, she needs to locate them. The Texas A&M University Libraries’ Quick Search will show where the book is located and whether the book is checked out.

Why should Emma choose books instead of another format? Books can provide an overview of a broad topic. Often, the author has gathered the information from multiple sources and created an easy to understand overview. Emma can later look for corroborating evidence in government documents and journal articles. Books are a good information resource for this stage of her research.

Once Emma starts to locate useful information resources, she realizes that there are further gaps in her knowledge. How does she decide which books to use? She needs the most current information because she certainly doesn’t want to get caught citing outdated information.

Looking at the publication date will help her to choose the most recent items. How can she get these books? She is not a Texas A&M University student or faculty member.

Interlibrary loan services at her public library will allow her to access books from an academic library or the college in her area may allow community members to borrow materials. There is a wealth of knowledge contained in the resources of academic and public libraries throughout the United States. Single libraries can’t hope to collect all of the resources available on a topic. Fortunately, libraries are happy to share their resources and they do this through interlibrary loan. Interlibrary loan allows you to borrow books and other information resources regardless of where they are located. If you know that a book exists, ask your library to request it through their interlibrary loan program. This service is available at academic libraries and at most public libraries.

Checking for Further Knowledge Gaps

Emma has had a chance to review the books that she chose and although her understanding of the issues associated with fracking has improved, she still needs more specific information from the point of view of the energy industry, the government, and the scientific community. Emma knows that if she doesn’t investigate all points of view, she will not be able to speak intelligently about the issues involved in the fracking debate. Where will she get this information? Because this information should be as current as possible, much of it will not be available in book format. Emma will need to look for scholarly journal articles and government documents. It is not likely that the public library will have the depth and scope of information that Emma now needs. Fortunately, Emma has just enrolled in a class at Texas A&M University and is able to use the resources at this academic library. However, when Emma visits the library, she finds that the amount of information available is overwhelming. There are many databases that will help Emma find journal articles on almost any topic. There are also many kinds of government information, some in article format, some as documents, and some as published rules and regulations. Emma suddenly feels out of her element and doesn’t have any idea of where to start her research.

Databases

Emma should start her search for journal articles with research databases. Research databases contain records of journal articles, documents, book chapters, and other resources. Online library catalogs differ from other research databases in that they contain only the items available through a particular library or library system. Research databases are often either broad or comprehensive collections and are not tied to the physical items available at any one library. Many databases provide the full text of articles and can be searched by subject, author, or title. Another type of database provides just the information about articles and may provide tools for you to find the full text in another database. The databases that contain resources for a vast array of subjects are referred to as general or multidisciplinary databases. Other databases are devoted to a single subject and are known as subject-specific databases. Databases are made up of:

- Records. A record contains descriptive information that is pertinent to one item which may be a book, a chapter, an article, a document, or other information unit.

- Fields. These are part of the record and they contain information that pertains to one aspect of an item such as the title, author, publication date, and subject.

- The subject field can sometimes be labeled subject heading or descriptor. This is the field that contains controlled vocabulary. Controlled vocabulary in a database is similar to controlled vocabulary in a Library Catalog, but each database usually has a unique controlled vocabulary unrelated to Library of Congress classifications. Many databases will make their controlled vocabulary available in a thesaurus. If the database you are searching does not have a thesaurus, use the subject field in a record to find relevant subject terms.

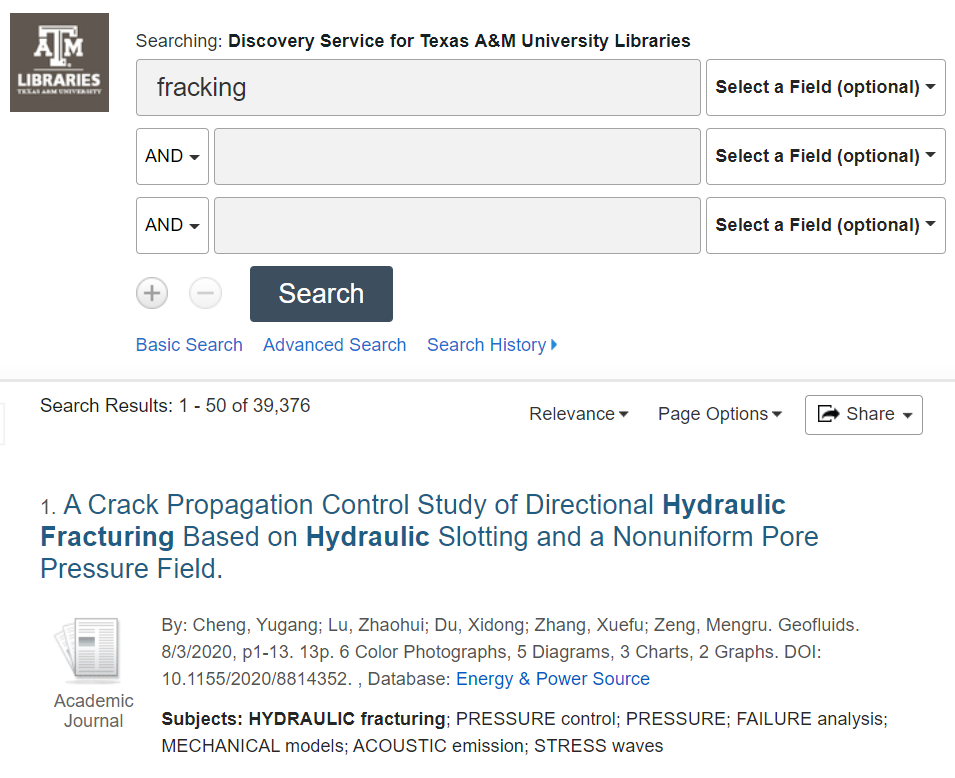

Below in Figure 7.5.2[2] is Emma’s search in the Quick Search database on the library homepage. The Quick Search includes sources from a number of different databases as well as the library catalog, so it’s a good place to start if you’re not quite sure which database to try. Emma typed the word fracking in the search box, but when she looks at her results, she sees that the term hydraulic fracturing is listed as a subject term. This tells Emma that hydraulic fracturing may be the term the library uses for fracking. She can add hydraulic fracturing to her search terms by entering fracking OR hydraulic fracturing in the search box. Once she has revised her search to include the controlled vocabulary term, she will want to limit her search results to the most relevant sources.

Boolean Operators

One way to limit a database search is to use the Boolean operators discussed earlier in section 7.3. Remember that Boolean operators are the words AND, OR, and NOT and you can use them in a database search to narrow or broaden your search results. You can usually find these words in the advanced search query area of a database.

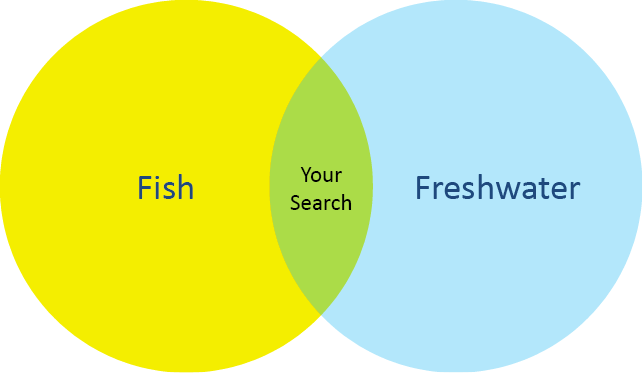

AND

And will narrow your search. For example, if you are interested in freshwater fishing you would enter the terms fish AND freshwater. Your results would then include records that only contained both of these words. The green overlapping area in Figure 7.5.3[3] represents the results from the fish AND freshwater search.

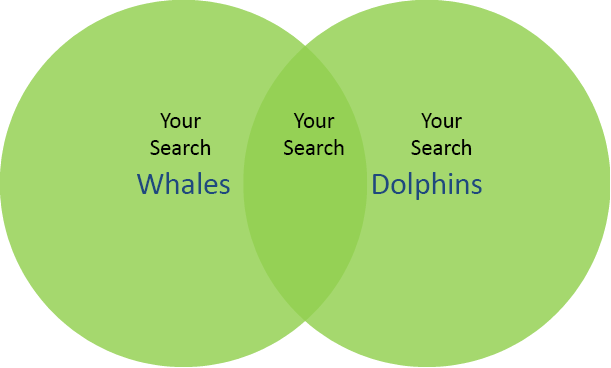

OR

OR will broaden your search and is usually used with synonyms. If you are interested in finding information on mammals found in the Atlantic Ocean, you could enter the terms whales OR dolphins. The circles below in Figure 7.5.4[4] represent the OR search. All of the records that contain one or another, or both of your search terms, will be in your results list.

NOT

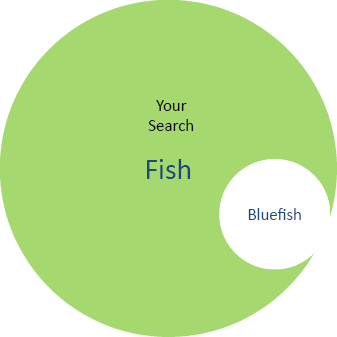

NOT will eliminate a term from your results. If you were looking for information on all Atlantic Ocean fish except Bluefish, you would enter fish NOT bluefish. The larger green circle in Figure 7.5.5[5] represents the results that you would retrieve with this search.

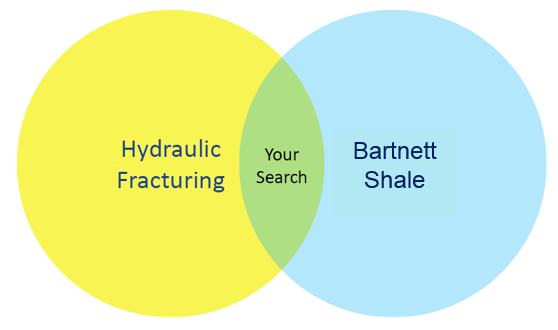

Let’s go back to Emma’s search in the TAMU Libraries’ Quick Search Database. If you remember, she searched the controlled vocabulary term, hydraulic fracturing. She can use AND with the phrase “Bartnett Shale” to focus and limit her results. Emma’s search query is now hydraulic fracturing AND “Bartnett Shale.” You can see this represented below in Figure 7.5.6 [6] The overlapping area represents the records this search will retrieve.

Database searching can seem confusing at first, but the more you use databases, the easier it gets and most of the time, the results you are able to retrieve are superior to the results that you will get from a simple internet search.

Other Information Sources

After taking some time to think about her goal, which is to present a persuasive argument on why she would be a good candidate for public office, Emma decides to concentrate on obtaining relevant government information. After all, she hopes to become part of the government, so she should have some knowledge of the government’s role in the fracking issue.

Government information consists of any information produced by local, state, national, or international governments and is usually available at no cost. However, sometimes it is reproduced by a commercial entity with added value. Look for websites that are created by official government entities, such as the U.S. Department of the Interior at http://www. doi.gov/index.cfm and Congress.gov, the congressional website. Texas’ website can be found at https://texas.gov/. It contains information from all Texas government branches. As Emma will discover, you can usually find a wealth of reliable information in government sources.

Even though she has narrowed the scope of her search for information resources, Emma is still confronted with a myriad of information formats. With help from a reference librarian, Emma discovers a research guide on government information available in the library. She notices that there is a section for Texas that she can explore.

She breathes a sigh of relief when she finds a link to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality’s website, which has many documents and regulations on the topic of Hydraulic Fracturing. The reference librarian continues to assist Emma to find the most useful information as she navigates through the site. Since this information is freely available to the public, Emma is able to access the site from home and spends many hours reading the documents.

Practice Activity

This section contains material from:

Bernnard, Deborah, Greg Bobish, Jenna Hecker, Irina Holden, Allison Hosier, Trudi Jacobson, Tor Loney, and Daryl Bullis. The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook, edited by Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson. Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014. http://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Archival link: https://web.archive.org/web/20230711202425/https://milneopentextbooks.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/

- “Information Sources from Less In-depth to More In-depth” derived in 2019 from: Deborah Bernnard et al., The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook, eds. Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson (Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014), https://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. ↵

- “TAMU Libraries Quick Search Results” is a July 2019 screen capture of the Texas A&M University Libraries catalog search results listing at https://library.tamu.edu. ↵

- “AND Venn Diagram” derived in 2019 from: Deborah Bernnard et al., The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook, eds. Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson (Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014), https://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. ↵

- “OR Venn Diagram” derived in 2019 from: Deborah Bernnard et al., The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook, eds. Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson (Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014), https://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. ↵

- “NOT Venn Diagram” derived in 2019 from: Deborah Bernnard et al., The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook, eds. Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson (Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014), https://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. ↵

- "Venn Diagram of Emma's Search" was derived by Sarah LeMire in 2019 from: Deborah Bernnard et al., The Information Literacy User’s Guide: An Open, Online Textbook, eds. Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson (Geneseo, NY: Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library, 2014), https://textbooks.opensuny.org/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. ↵

Government documents are texts and information produced by government agencies. They can include research data, policy papers, maps, recommendation reports, statistics and forecasts, census and demographic data, meeting transcripts, and more.

This is how information is spread throughout a community. Information dissemination is a process, and usually information will be shared with others in changing formats over time.

An agreed-upon term or phrase use to consistently describe an item or concept. For instance, "carbonated beverages" is a controlled vocabulary term for a soda/pop/soft drink.

A library catalog is a database of records for the items a library holds and/or to which it has access. Searching a library catalog is not the same as searching the web, even though you may see a similar search box for both tools. Library catalog searches can return information that you would not find on the open web, and the searching process will likely take longer to refine.

A discovery interface type of library catalog search that appears similar to a search engine. It often searches article databases in addition to catalog holdings such as books and videos.

With regard to texts, format refers to how words and/or images are arranged on a page. With regard to information and library searches, format refers to the medium of the information, such as a book, ebook, article, audio recording, etc.

Query: to ask a question or make an inquiry, often with some amount of skepticism involved.