Audience

Your audience is the person (or people) reading or using what you write. Throughout this book, audience, reader, recipient, and user are used interchangeably to designate your audience. Understanding audience and all that term encompasses is one of the most important and challenging tasks you will face on the job. Once you begin the work of understanding and addressing the concept of audience, you are on your way to being a successful professional and technical writer.

When we begin to write, one of our most pressing questions is who is my audience? Why? Because we are not writing a person-less paper to no one. If we think about our actual readers, we often can identify them as members of our own communities or stakeholders in other communities who will be affected by the ideas we offer about the problem at hand. But how do we take these people into account when we produce a report, an argument, a brochure, a PSA, a manual, or a proposal—and the list goes on. How do we develop audience awareness for the various types of documents we might create in academic, professional, and public settings?

We know that talking out a problem with others requires us to interact—to listen, respond, and reflect, to give and to take. How often in a conversation or class discussion have you said, “I can relate” before giving your opinion? This same conversational give-and-take can be applied to situations where you dig into a pressing workplace or community problem. On the page, when we “relate”—when we approximate a lively conversation between ourselves and our stakeholders—we can write more effectively and be taken more seriously.

Stakeholders: a synonym for audience. Stakeholders are other people with the same question as I have about the problem, the people causing the problem, the people impacted by the problem, or the people who think they have a better answer than I do. They may be like-minded, hostile, of two minds, or noncommittal. However, we may not know where they stand unless we talk to them. While this may be possible, it’s not likely that in all situations we can have a one-on-one with people who might care about what we have to say.

So, how can we write texts that include our audience in the buzz going on in our heads? Read what others have to say relevant to our problem. Our research provides a foundation for our inquiry. We can draw on others to establish the background on the problem, to discover what like-minded writers have said that can support our arguments, and to recognize what hostile writers have argued so we can respond intelligently.

Entering this course, you probably already have had experience writing a research paper in this way.

As well as being an important factor in our research process, our audience is also integral to our writing process. In the early phase of generating ideas, we can imagine our audience into being when we use our sources as a sounding board. The person who shares our view, the person who vehemently disagrees, and the one who is on the fence—we can write directly to them, and then as our drafts unfold, we can weave that conversation into our lines of reasoning.

If I were in class, I would say to that student, clearly a stakeholder like in a business role wants to solve the problem of connecting with their audience: Good point. I have just given you some ideas for building audience awareness that you can use to write a strong academic essay—one in which you are effectively interacting with your sources and your stakeholders. However, let’s think about how we can apply writing our audience into other types of texts. What does that lively conversation look like?

Audience Analysis Questions

To answer the audience question, you need to perform an audience analysis. Here are some broad questions to get you started:

What type of person/people will be reading the document?

For example:

Why is your audience reading the document (notice the relationship to purpose)?

For example:

How will your audience use your document (notice the relationship to design)?

For example:

Where and how will they engage with the document? Will they be reading your document online, using it in hard copy in a lab environment, viewing it in a meeting, etc.?

Audience analysis means you need to consider the type, knowledge, physical location, disposition, experience, interest and expectations of your potential audience(s). You’ll want to pay close attention to cultural factors, as well. Differences in culture significantly inform whether your document will be effective in communicating to your audience and achieving its goal.

When it comes down to it, whatever kind of document we are producing, we want our audience to take us seriously. Two basic questions can guide us: What is the problem about? Who cares about the problem?

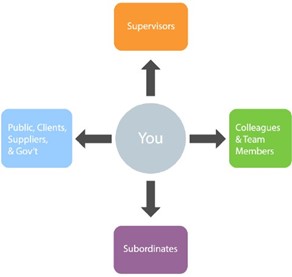

Audience analysis is possibly the most critical part of understanding the rhetorical situation. See Figure 2 below. Is your audience internal (within your company) or external (such as clients, suppliers, customers, other stakeholders)? Are they lateral to you (at the same position or level), upstream from you (management), or downstream from you (employees, subordinates)? Who is the primary audience? Who are the secondary audiences? These questions, and others, help you to create an understanding of your audience that will help you craft a message that is designed to effectively communicate specifically to them.

Keep in mind that your different audiences will also have a specific purpose in reading your document. Consider what their various purposes might be, and how you can best help them achieve their purpose. What do they already know? What do they need to know? Considering what they are expected to do with the information you provide will help you craft your message effectively. Consider also that technical writing often has a long “lifespan” – a document you write today could be filed away and reviewed months or even years down the road. Consider the needs of that audience as well.

| Audience | Purpose for Reading |

|---|---|

| Executives | Make decisions |

| Supervising Experts/Managers | Advice decision makers; direct subordinates |

| Technical Experts/Co-Workers | Implement decisions; advise |

| Lay People/Public/Clients | Become informed; choose options; make decisions |

From here, we can begin writing the conversation into our unfolding drafts. If our readers can locate themselves in our texts and feel as if we are co-collaborators in problem- solving, we go a long way in creating an ethos they trust. We also function as an organizational author. When you write a memo, email, proposal, or other official business communication, you are writing as the organization. You represent the organization to the reader since you are the person analyzing what type of writing would be best suited for an intended audience.

Works cited in this section:

Graff, G., & Birkenstein, C. (2014). They say, I say: The moves that matter in academic writing (p. 245). New York: WW Norton & Company.

Media Attributions

- Private: Figure 2