Creating Interview and Survey Questions

To prepare for several types of primary research (mainly interviews, polls, and surveys) you will need to create questions. The content of the questions should align with your research goals. These questions can be divided into two types—open-ended questions and closed-ended questions.

Before you begin drafting your surveys, interviews, or polls, you should learn as much about the topic—and your sample—as possible. Conducting secondary research on the topic and sample can help you get a solid foundation for your primary research. This will help you construct questions that glean solid data and help you tailor the research to the respondent(s). Then, construct your interview, survey, and poll questions to help “fill in the gap” created by missing or incomplete research on the topic.

Writing Open-Ended Questions

Open-ended questions are structured to encourage detailed responses which focus on the respondent’s experiences or feelings. The point is to encourage a lengthier answer; these questions should be asked in a way that requires more than a “yes/no” response. Open-ended questions are especially important for interviews. For example, you may ask someone, “What do you think about the candidates running for mayor?” This is an open- ended question that encourages a detailed response. To create open-ended questions, it is helpful to begin the question with words and phrases such as explain, describe, tell me about, or walk me through your experience with…

Writing Closed-Ended Questions

Closed-ended questions are structured to limit the available responses, usually to a single word, number, or phrase option. In the case of survey and poll questions, you can limit the response even further by providing answer choices. A closed-question version of the mayor example above is, “Which candidate for mayor do you like the most?” with the candidates’ names listed as answer options. Or “Do you believe the current campus dining options provide enough variety for vegetarian diners?”

Question Types

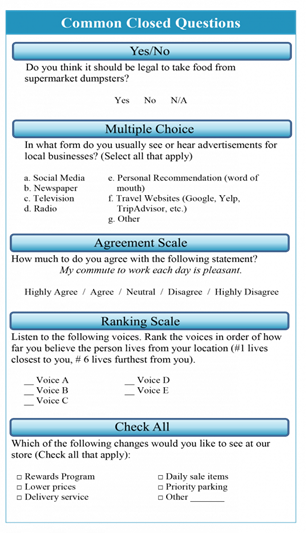

When you create closed questions for a survey or poll, you will also make decisions about the type of questions you use. There are several types of common question types to choose from, including but not limited to: Ranking Scales, Agreement Scales, Yes/No Questions, Multiple Choice, and Check All That Apply.

The type of question you choose will depend on the type of information you want to know. Below are two similar questions and answer options; however, the type of data gathered will be different. Imagine you are researching different types of campus improvements. If you ask students to “Check all that apply,” you can see which ideas are generally popular or unpopular. If you ask the students to “Rank” the ideas, you can use the data to infer which is the most popular, second most popular, and so forth. It is a slight distinction but can make a difference during data analysis.

Creating Answers

You must give appropriate response choices for all closed questions. The type of responses will vary according to what type of info you need to know, how you can get as much variation/good data as possible, and the type of question you ask. You should include at least one null answer option for most questions. For example, no answer, prefer not to answer, or other. This option allows respondents to answer questions when their option is not provided and/or continue the survey if a question makes them uncomfortable.

Common Issues

Regardless of whether you create an open or closed question, you should avoid

negatively worded questions, double-barreled questions, and biased questions.

- Negatively worded questions: ask for negative data. For example, if you asked, “How many times per week are you unable to access the door lock after hours?” you are asking for how many times something does not occur. This type of phrasing can confuse some respondents, which could lead to bad data. It is best to revise these questions to ask for a positive amount, such as “How many times per week are you able to access the door lock after hours?”

- Double-barreled questions: ask about two or more ideas, such as, “How many times per week do you speak with staff and administration when you have a problem?” This question asks about two different ideas—speaking with staff and speaking with administration. The amount of contact per week could vary greatly between these two groups. In cases such as these, revise the question to address only one topic or split into multiple questions.

- Biased questions: make assumptions about the respondent or lead the reader to an answer. For example, “How many times a week do you encounter the terrible seating situation at the Student Union?” will encourage your audience to view the seating situation as “terrible” even if they had not previously considered the situation to be problematic. It can be difficult to not implant ideas, confuse the participant, or compile misleading information. For example, imagine you work for an ice cream company, and need to prove that chocolate ice cream is the most popular flavor. You ask in your survey, “Do you like chocolate ice cream?” Respondents will probably say “yes.” However, this is not a complete survey. Just because a person likes chocolate ice cream does not mean it is the most popular flavor. Instead, you should ask several questions, one of which might specifically ask respondents to reveal their favorite ice cream flavor.

At other times, you may lead the respondent with phrasing or make assumptions of how the respondent answered earlier questions. For example, if you are doing research over extending library hours, you could ask:

- Do you think the library should extend their hours?

- Yes / No / Maybe / NA

- When should they extend their hours?

- 4-6am / 12- 2am / Open 24 hours

- What technology do you want to improve at the library?

- Printers / more computers / more outlets

In the above example, the second question is written as though the answer to the first question will be Yes, but that may not be the case. What if the person answered No or Maybe to the first question? The second question has no option to allow for dissent or disagreement. Also, question three assumes that the respondents want to improve something technology-related (without them saying so), and the responses limit the answers to only three areas of technological improvement.

Once you have decided on the type of information you need from your surveys or interviews, make sure you go back and revise your question structure and phrasing to avoid bad data through negatively worded questions, double-barreled questions, and biased phrasing.

Media Attributions

- Private: Figure 8: Common Closed Questions

- Private: Figure 9: Similar Questions, Different Data Results