Writing Style

Believe it or not, there is no single, magic writing style. There is also no such thing as good style or bad style because style is the individual way you write. Following some general strategies can make your writing stronger and more effective, but you must decide when, where, and how to apply them.

You may have heard or been told some “easy rules” about writing style. Two of the more common theories are the CBS (clarity, brevity, sincerity) theory and the 4 C’s (clear, concise, consistent, coherent). While both theories provide easy-to-remember mnemonics, their usefulness is rather limited because, by their very nature, they limit style options and reduce style decisions to three or four steps. In practice, style is more complicated than a few simple steps.

Carolyn Rude has written a definition of style that is particularly useful and is a good starting place for style:

Style is “the cumulative effect of choices about words, their forms, and their arrangement in sentences.”

Her definition is helpful because it emphasizes the choices you make, as the writer. It also emphasizes words and sentences, which is the primary goal of talking about style in this course: to help you to start paying more attention to what you write.

While your style is your own, there are tips and techniques to make your personal style evolve into “good writing.” “Good writing” is effective writing, meaning that your ideas can be understood by your audience, for your particular purpose, and in a specific context.

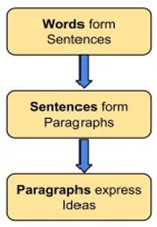

When you are writing on the job, you must pay close attention to what you’re writing and how you’re writing. To get you started looking at your writing, let’s break your writing down into three parts (see Figure 4).

Writing effectively (and ineffectively) begins with words then sentences and then paragraphs. Following are some suggestions to guide the development of your writing style.

Words

Word choice is the basis of writing style. Careful word selection is vital to effective communication. Don’t be shy about looking up definitions of words to make sure you are using the correct word and using it correctly. Especially when you are communicating to a technical or specialized audience, it’s vital that you are using the terms and ex-pressions the audience expects and is habituated to—and that you are using them in the right way at the right time.

Here are some additional considerations when selecting words:

- Use words that are appropriate for and/or familiar to the audience you are addressing

- Use active verbs

- Use concrete words that draw on the reader’s senses and that the reader can experience or relate to in some way

- Put modifiers—adjectives, adverbs, participles—close to the word they modify

- Think beyond what a word denotes (its definition) to what it connotes (how it makes the reader feel, e.g., stubborn vs. persistent; or aggressive vs. assertive)

Sentences

Professional and technical writing emphasizes action—that is, your audiences do something with your writing after reading your work. It’s important, therefore, to clearly communicate your goal with each sentence. In general, then, you will want to include one idea in each sentence. This is especially true when communicating complex ideas and information. When the level of sophistication of your over-arching concept or goal goes up, it’s especially important that your individual sentences are simple and direct. Your audience is asked to absorb one idea one sentence at a time, then you can use transitional words or phrases to establish relationships between ideas building toward the larger concept or goal.

Here are some words you can use to establish relationships be-tween sentences:

- Addition: again, also, besides, and, equally important, finally, furthermore, in addition, likewise, moreover, first, second, third, etc.

- Clarification: clearly, evidently, of course, too.

- Comparison: likewise, similarly

- Contrast: after all, although, at the same time, but, however, in contrast, nevertheless, on the contrary, on the one hand, on the other hand, still, yet.

- Exemplification: for example, for instance, that is, thus.

- Result: accordingly, as a result, consequently, in short, there-fore, thus, hence

- Summary: in brief, in conclusion, in short, to conclude, to sum up, to summarize.

And here are some additional sentence-level guidelines:

Eliminate Wordiness

- Check the end of sentences for words and phrases that are unnecessary.

- Look for strings of prepositional phrases.

Construct sentences so they emphasize the important information.

- Shift less important ideas or information to the front of the sentence.

- Put the important information at the end.

- Do not bury your main point in a prepositional phrase.

Paragraphs

Paragraphs join the individual ideas of sentences together to make a point. Here are some general guidelines for paragraphs:

- Paragraphs have points

- One main idea should be developed in each paragraph

- Order paragraphs logically (e.g., from general to specific, known to unknown, etc. —See the “Organizing Information” chapter)

- Include topic sentences

- At or near the beginning of the paragraph

- Tell the reader what to expect from that paragraph

- Use transitions between paragraphs for unity

- See tips on transitional language in the Sentence section

- Make paragraphs cohere – within and between paragraphs

- Link information already presented to new information to show the logical connections between your ideas

- Begin paragraphs with idea that are familiar to your readers then move toward new, less familiar or more complex ideas.

End paragraphs with a statement summarizing what the paragraph accomplished and identify how the paragraph fits into your larger idea or goal.

Media Attributions

- Private: Figure 4