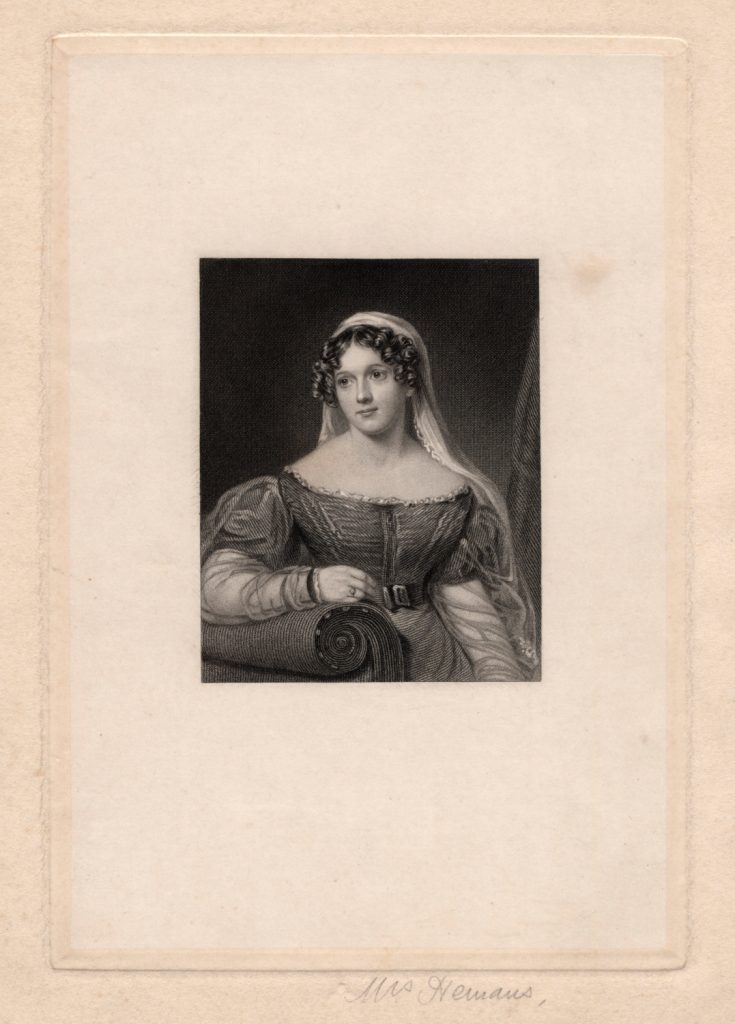

Felicia Hemans (1793-1835)

Biography

Felicia Dorothea Hemans was, in her lifetime, one of the most celebrated poets of the early nineteenth century. So popular, in fact, that only Byron outsold her.[1]

And yet despite her fame during her own time period, her name is often more familiar today to literary historians than to general readers. Born in Liverpool in 1793 to a father of Irish descent and a mother of German-Italian heritage, Hemans embodied a complexity—cultural, poetic, and personal—that defies easy classification. The tidy label “English poet” falters here, as does the later Victorian image of Hemans as the gentle “poetess” of hearth and home. Her own verse, as we’ll see, tells a far more complicated story.

Between 1808 and her death in 1835, Hemans published nineteen volumes of poetry, many in multiple editions, and her works circulated widely on both sides of the Atlantic. She was, quite simply, everywhere: in parlors, in periodicals, tremendously admired for her lyricism and moral sensibility. But this very accessibility would, ironically, contribute to her marginalization.

As the nineteenth century progressed, Hemans became framed not as a serious literary mind but as a model of domestic virtue: a “poet at home,” whose writing was often reduced to the sentimental.[2]

The reality, however, is far more interesting. While Hemans wrote powerfully from within the domestic sphere, she rarely limited herself to it. As Tricia Lootens observes, she deftly navigated the fraught boundary between public and private concerns, simultaneously embodying the role of national poet and the supposed modesty of the “poetess.”[3]

Her contemporary Byron, never one to resist a dig, mocked Hemans as “Mrs. Hewoman.” This jab was a reflection not only of Byron’s personal pique but also of broader cultural discomfort with women who spoke too boldly in public literary life.[4] Rather than accept the notion of Hemans as “unwomanly,” it is more accurate to read such critiques as symptoms of the anxieties surrounding gender, authorship, and authority that pervaded the Victorian era.

Hemans’s work was forged in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, during an time of reflection on empire, patriotism, and loss. Though she wrote before the full swell of Victorian imperialism, Hemans nevertheless grappled with the costs of war, the allure and danger of patriotic sacrifice, and the grief that lingers behind the pageantry of national glory.[5]

The Victorian period would reshape Hemans into a different figure altogether. Anthologies later packaged her as the emblematic “poetess”: safe, sentimental, domestic. This framing obscured the political critique, historical consciousness, and formal ambition that run through her work.[6]

These misreadings are precisely what recent scholarship has sought to correct. Hemans’s poetry speaks directly to enduring literary and cultural questions.

- How are women’s poetic identities shaped within gendered cultural frameworks?

- How is aesthetic value determined within specific historical contexts?

- How do we understand the relationship between Romantic and Victorian literary periods in light of poets like Hemans ? (After all, you are encountering her now in an anthology devoted to Victorian poetry; she also appears in collections devoted to Romanticism. How–and why–did I decide to include her here, and not in my Romanticism courses?)

- And how can we recover Hemans as a poet whose work critiques as much as it celebrates cultural ideals?

Hemans’s best-known poems fuse public commentary with intimate emotion. They weave together patriotism and its discontents: child martyrs, war widows, and broken families haunt her verses. Again and again, she shows us that the home is never truly separate from the world beyond its walls. The domestic is political. The personal always has public stakes.[7]

For readers and scholars alike, Hemans offers a way into the tensions at the heart of the Victorian era.

Standard Editions of Hemans’s Poetry

- Hemans, Felicia. Felicia Hemans: Selected Poems, Prose, Letters, and Reception Materials, edited by Susan J. Wolfson, Princeton UP, 2000.

- —. Felicia Hemans: Selected Poems, Prose, and Letters, edited by Gary Kelly. Broadview, 2002.

- —. Records of Woman: With Other Poems, edited by Paula R. Feldman, University Press of Kentucky, 1999.

- —.The Forest Sanctuary and Other Poems, edited by D. M. R. Bentley, Canadian Poetry Press, 2000.

- —.The Poems of Felicia Hemans, edited by Paula R. Feldman and Theresa M. Kelley, Associated University Presses, 1999.

Reference Texts and Biographical Studies

- Sweet, Nanora. “Hemans, Felicia Dorothea Browne.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford UP, 2004.

- Sweet, Nanora, and Julie Melnyk, eds. Felicia Hemans: Reimagining Poetry in the Nineteenth Century. Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

- Looser, Devoney, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Women’s Writing in the Romantic Period. Cambridge UP, 2015.

- The Poetess Archive, “About the Term ‘Poetess'”. https://www.poetessarchive.org/about.html

Select Literary Criticism, Edited Collections, Thematic Studies & Essays

- Anderson, Amanda. The Powers of Distance: Cosmopolitanism and the Cultivation of Detachment. Princeton UP, 2001.

- Armstrong, Isobel. Victorian Poetry: Poetry, Poetics, and Politics. Routledge, 1993.

- Behrendt, Stephen C., editor. Romanticism and Women Poets: Opening the Doors of Reception. Lexington UP, 1999.

- Blain, Virginia, et al., editors. The Feminist Companion to Literature in English: Women Writers from the Middle Ages to the Present. Yale UP, 1990.

- Clarke, Norma. Ambitious Heights: Writing, Friendship, Love—The Jewsbury Sisters, Felicia Hemans, and Jane Welsh Carlyle. Routledge, 1990.

- Curran, Stuart. Poetic Form and British Romanticism. Oxford UP, 1986.

- Feldman, Paula R. British Women Poets of the Romantic Era: An Anthology. Johns Hopkins UP, 1997.

- Feldman, Paula R., and Theresa M. Kelley, editors. Romantic Women Writers: Voices and Countervoices. UP of New England, 1995.

- Labbe, Jacqueline M. Romantic Visualities: Landscape, Gender and Romanticism. Macmillan, 1998.

- Lootens, Tricia. “Hemans and Home: Victorianism, Feminine ‘Internal Enemies,’ and the Domestication of National Identity.” PMLA, vol. 109, no. 2, 1994, pp. 239–252.

- Melnyk, Julie. “Hemans’s Later Poetry: Religion and the Vatic Poet.” Felicia Hemans: Reimagining Poetry in the Nineteenth Century, edited by Nanora Sweet and Julie Melnyk, Palgrave Macmillan, 2001.

- Lootens, Tricia. Lost Saints: Silence, Gender, and Victorian Literary Canonization. University Press of Virginia, 1996.

- Mellor, Anne K. Romanticism and Gender. Routledge, 1993.

- Newlyn, Lucy. Reading, Writing, and Romanticism: The Anxiety of Reception. Oxford UP, 2000.

- Pratt, Lynda. “Women, Poetry, and the Language of Public Discourse.” The Cambridge Companion to British Romanticism, edited by Stuart Curran, Cambridge UP, 2010, pp. 173–193.

- Ross, Marlon B. The Contours of Masculine Desire: Romanticism and the Rise of Women’s Poetry. Oxford UP, 1989.

- Sweet, Rosemary. Cities and the Grand Tour: The British in Italy, c.1690–1820. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Wolfson, Susan J. Borderlines: The Shiftings of Gender in British Romanticism. Stanford UP, 2006.

Reading Questions

-

Hemans was born to parents of Irish and German-Italian heritage, yet she is categorized as an English poet. How does this complicate our understanding of her place in Victorian literary history? What implications does this have for how we define national literary traditions?

-

The term “poetess” came to signify a particular style of poetry associated with sentimentality and domesticity. How did this label affect Hemans’s reception, both in her lifetime and in later literary history? Can you think of modern parallels where labels have shaped or limited a writer’s legacy?

-

Hemans is described as navigating the tension between public authorship and private domestic identity. How do her life and work reflect this balancing act? How might this tension show up in the content or tone of her poetry?

-

Byron’s mocking nickname “Mrs. Hewoman” reflects anxieties about women writers in the early nineteenth century. How does this kind of gendered critique continue to shape the reception of women’s writing today? How might a contemporary feminist reading approach Hemans differently?

-

Hemans’s poetry both commemorates national heroes and critiques the violence of war. How does her work complicate the idea of patriotic duty? What emotions or moral reflections does she invite in her depictions of wartime loss?

-

The text describes how literature anthologies reshaped Hemans’s image and selectively preserved parts of her work. What does this tell us about how literary canons are formed? How do you think decisions about which authors and texts are taught or remembered impact cultural memory?

-

The final section emphasizes that for Hemans, “the domestic is political.” What does this mean in the context of her poetry? How can the experiences of home and family reflect or resist larger social and political forces?

-

Recent scholarship invites readers to recover Hemans as a more complex literary figure. Based on this biographical entry, what aspects of her life and work seem most relevant to today’s cultural or literary conversations? Why does Hemans matter now?

- Hemans's popularity in the 1820s rivaled that of Byron, whose celebrity was unmatched. Her widespread readership made her one of the best-known poets of her generation. ↵

- The term “poetess” came to signify a sentimental, morally uplifting, and domestic style of poetry often associated with women writers. Over time, this label was used to diminish the perceived literary value of their work. The Poetess Archive has a great section on the history of the term "poetess" and its many complications. See Suggested Reading. ↵

- Navigating the public/private divide was essential for women writers of this era. Many balanced the need for public authorship with cultural expectations of feminine modesty and domesticity. ↵

- Byron's views reflect broader tensions about gender, authorship, and the public role of women writers, which colored critical reception of female poets. ↵

- The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) shaped the political and cultural climate of early nineteenth-century Britain, leaving lasting impacts on literature and national identity. ↵

- Influential literary anthologies helped shape the literary canon. Hemans’s inclusion in these collections often emphasized her domestic verse over her more radical writings. ↵

- This idea echoes later feminist criticism, which asserts that the personal and the political are deeply intertwined—a concept applicable to Hemans's work and to broader cultural critique. ↵