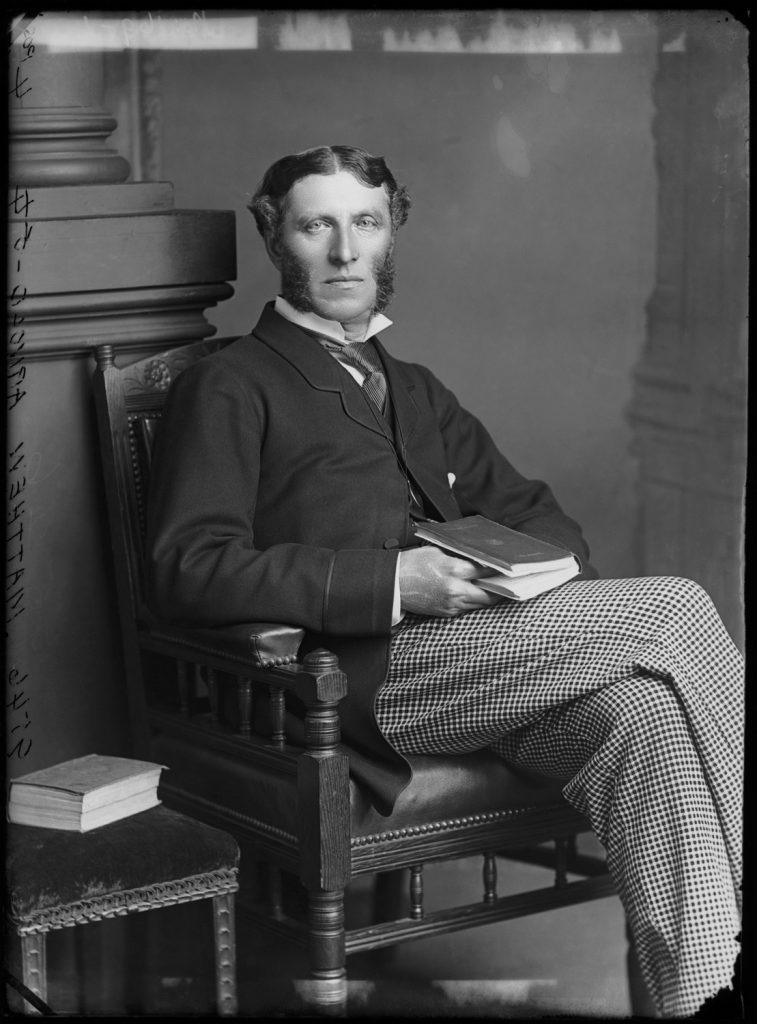

Matthew Arnold (1822-1888)

Matthew Arnold, one of the defining voices of Victorian poetry and criticism, was born in 1822 in the village of Laleham-on-Thames. Arnold’s early education included time at Winchester College before he entered Rugby School in 1837, where his father, Dr. Thomas Arnold, served as headmaster. Thomas Arnold was not only a clergyman but also a leading figure of the Broad Church movement in Anglicanism, which promoted a liberal theological stance in contrast to the Oxford Movement led by John Henry Newman. Dr. Arnold’s deep commitment to moral and social reform through education profoundly influenced Matthew, though the younger Arnold sought to distinguish himself from his father’s stern earnestness.

At Oxford University (Balliol College), Matthew Arnold cultivated a reputation as a dandy. Some biographers dismiss this persona as a temporary mask, but it arguably infused his mature prose with wit and geniality. In 1843, Arnold won the Newdigate Prize for his poem “Cromwell”, and in 1845 he was elected a fellow of Oriel College. This academic success set the stage for his dual career as both public servant and writer.

In 1847, Arnold became private secretary to Lord Lansdowne. In 1851, the year of his marriage to Frances Lucy Wightman, he accepted the role of Inspector of Schools, a post he would hold until 1886. This work, often monotonous, took him across Britain and into Europe (France, Germany, Switzerland), offering firsthand insights into the lives of the middle class. Arnold came to believe that improving education for this social group was the most pressing need of his time, a conviction that shaped both his educational and cultural writings.

Arnold as Poet

Arnold’s poetic reputation rests on his ability to capture the philosophical and emotional currents of his age, often through evocative depictions of nature. In works like “Thyrsis” and “The Scholar-Gipsy,” natural settings do more than provide scenic backdrops; they unify and deepen the emotional resonance of the poems. He frequently drew on personal experiences, exploring themes of loneliness, the longing for serenity, the melancholy of lost youth, and despair in a universe where humanity’s role seemed precarious. This vision was later shared by poets such as Thomas Hardy.

In this way, Arnold can be seen as a forerunner to T. S. Eliot and W. H. Auden, offering a poetic record of personal and societal malaise. Yet Arnold believed poetry must do more than reflect despair. It must bring something restorative. In his influential Preface to Poems (1853),[1] he argued that poetry must offer an “architectonic” unity, inspire joy, and help readers transcend suffering through action and reflection. As he wrote to his friend Arthur Hugh Clough, poetry should do more than awaken “pleasing melancholy”; it must “inspirit and rejoice the reader.”

Arnold as Literary Critic

Arnold’s contributions to literary criticism are foundational. His two volumes of Essays in Criticism (1865, 1888) advance the idea that literature should cultivate moral and intellectual virtues. He celebrated writers such as Homer, Wordsworth, Tolstoy, and Marcus Aurelius for embodying “high seriousness,” a central tenet of his critical philosophy. Although he admired the rich language of poets like Keats and Tennyson, he preferred a more restrained, classical style. He valued clarity, unity, and moral purpose over ornate expression.

Arnold also introduced the concept of “touchstone” passages: brief excerpts from great works that could serve as benchmarks for literary excellence.[2] His vision of criticism was “disinterested.” Criticism, he argued, should not serve political or personal agendas but should aim to elevate the cultural conversation.

Arnold and Religion

In his later writings, Arnold addressed the religious skepticism of the Victorian era. In works like Literature and Dogma and God and the Bible, he advanced a form of liberal Anglicanism infused with agnostic tendencies. His poetry, particularly “Dover Beach,” reflects the emotional and spiritual dislocation brought about by the decline of traditional faith. This theme continues to resonate deeply with modern readers.

Suggested Readings

Standard Editions of Arnold’s Poetry

- Arnold, Matthew. The Poems of Matthew Arnold. Edited by Kenneth Allott, revised by Miriam Allott, Longman, 1979.

- Arnold, Matthew. The Poetical Works of Matthew Arnold. Edited by C. B. Tinker and H. F. Lowry, Oxford UP, 1950.

- Arnold, Matthew. Selected Poems of Matthew Arnold. Edited by Miriam Allott, Routledge, 1994.

Reference Texts and Biographical Studies

- Arnold, Matthew. The Complete Prose Works of Matthew Arnold. Edited by R. H. Super, 11 vols., U of Michigan P, 1960–1977.

- Honan, Park. Matthew Arnold: A Life. McGraw-Hill, 1981.

- Super, R. H. Matthew Arnold. Twayne Publishers, 1970.

Key Literary Criticism, Edited Collections, and Thematic Studies

- Allott, Miriam, editor. Matthew Arnold: The Critical Heritage. Routledge, 1975.

- Anderson, Amanda. The Powers of Distance: Cosmopolitanism and the Cultivation of Detachment. Princeton UP, 2001.

- Armstrong, Isobel. Victorian Poetry: Poetry, Poetics, and Politics. Routledge, 1993.

- Beaumont, Matthew. Victorian Poetry and the Politics of Metre: Tennyson to Hardy. Cambridge UP, 2019.

- Bloom, Harold, editor. Modern Critical Views: Matthew Arnold. Chelsea House, 1987.

- Carnall, Geoffrey. “Matthew Arnold’s ‘Great Critical Effort.’” Essays in Criticism, vol. 8, no. 3, 2020, pp. 256–270.

- Collini, Stefan. Matthew Arnold: A Critical Portrait. Oxford UP, 1994.

- Cousins, James Walter. Arnold’s Poetic Landscapes. Yale UP, 1973.

- Eliot, T. S. The Use of Poetry and the Use of Criticism. Faber and Faber, 1933.

- Keep, James. Matthew Arnold and the Betrayal of Language. U of Virginia P, 1986.

- Lecourt, Sebastian. “Matthew Arnold and the Institutional Imagination of Liberalism.” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 49, no. 2, Summer 2021, pp. 361–375.

- Neiman, Fraser, editor. Matthew Arnold: The Critical Heritage. Routledge, 1995.

- O’Gorman, Francis. Matthew Arnold and the Art of the Negative. Ashgate, 2005.

- Rahayu, Anik Cahyaning. “Three Critical Approaches in Literary Criticism: An Example Analysis on Matthew Arnold’s ‘Dover Beach.’” ANAPHORA: Journal of Language, Literary and Cultural Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, 2020, pp. 64–72.

- Ricks, Christopher. T. S. Eliot and Prejudice. Faber and Faber, 1988.

- Sangwan, Kajal. “Loneliness and Despair in the Selected Poems of Matthew Arnold.” Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science, vol. 10, no. 5, 2022, pp. 74–76.

- Tucker, Herbert F. Victorian Literature and Culture. Blackwell, 1999.

- Trilling, Lionel. Matthew Arnold. Norton, 1939.

- Ward, T. H., editor. The English Poets: A Literary History. Macmillan, 1880.

- Arnold's Preface to Poems (1853) is essential reading for understanding his view that poetry should be not only emotionally moving but also intellectually and morally instructive. ↵

- The “touchstone method” is one of Arnold’s most influential contributions to literary criticism, inviting readers to use short exemplary passages as a standard for judging literary quality. ↵