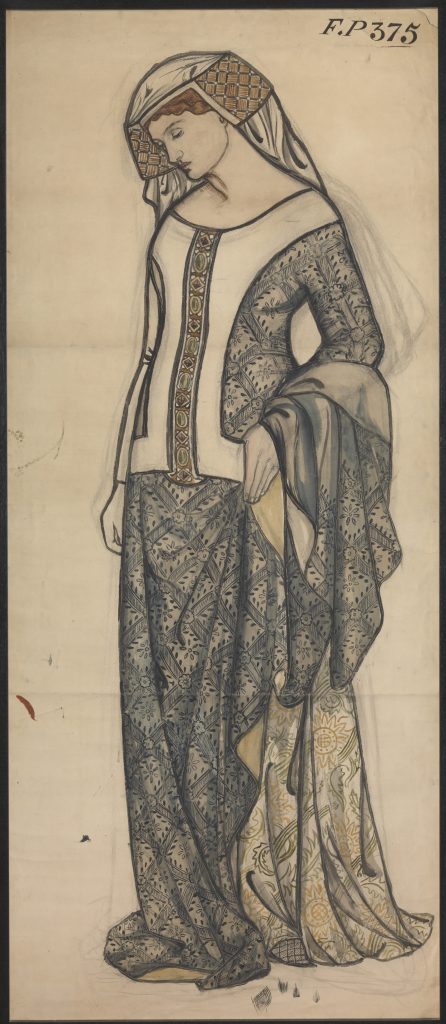

William Morris (1834-1896)

“The Defence of Guenevere” (1858)

Overview and Annotations

Coming soon.

Authored by Alexa Garcia.

BUT, knowing now that they would have her speak,

She threw her wet hair backward from her brow,

Her hand close to her mouth touching her cheek,

As though she had had there a shameful blow,

And feeling it shameful to feel ought but shame

All through her heart, yet felt her cheek burned so,

She must a little touch it; like one lame

She walked away from Gauwaine, with her head

The tears dried quick; she stopped at last and said:

O knights and lords, it seems but little skill

To talk of well-known things past now and dead.

And pray you all forgiveness heartily!

Because you must be right, such great lords; still

And you were quite alone and very weak;

Yea, laid a dying while very mightily

Of river through your broad lands running well:

Suppose a hush should come, then some one speak:

Now choose one cloth for ever; which they be,

I will not tell you, you must somehow tell

Yea, yea, my lord, and you to ope your eyes,

At foot of your familiar bed to see

Not known on earth, on his great wings, and hands,

Held out two ways, light from the inner skies

Seem to be God’s commands, moreover, too,

Holding within his hands the cloths on wands;

Wavy and long, and one cut short and red;

No man could tell the better of the two.

‘God help! heaven’s colour, the blue;’ and he said, ‘hell.’

Perhaps you then would roll upon your bed,

‘Ah Christ! if only I had known, known, known;’

Launcelot went away, then I could tell,

And roll and hurt myself, and long to die,

And yet fear much to die for what was sown.

Whatever may have happened through these years,

God knows I speak truth, saying that you lie.

But as it cleared, it grew full loud and shrill,

Growing a windy shriek in all men’s ears,

She said that Gauwaine lied, then her voice sunk,

And her great eyes began again to fill,

But spoke on bravely, glorious lady fair!

Whatever tears her full lips may have drunk,

Spoke out at last with no more trace of shame,

With passionate twisting of her body there:

To dwell at Arthur’s court: at Christmas-time

This happened; when the heralds sung his name,

Along with all the bells that rang that day,

O’er the white roofs, with little change of rhyme.

And over me the April sunshine came,

Made very awful with black hail-clouds, yea

And bowed my head down: Autumn, and the sick

Sure knowledge things would never be the same,

Of blossoms and buds, smote on me, and I grew

Careless of most things, let the clock tick, tick,

My eager body; while I laughed out loud,

And let my lips curl up at false or true,

Behold my judges, then the cloths were brought;

While I was dizzied thus, old thoughts would crowd,

By Arthur’s great name and his little love;

Must I give up for ever then, I thought,

Glorifying all things; for a little word,

Scarce ever meant at all, must I now prove

Will that all folks should be quite happy and good?

I love God now a little, if this cord

Make me love anything in earth or heaven?

So day by day it grew, as if one should

Down to a cool sea on a summer day;

Yet still in slipping there was some small leaven

Until one surely reached the sea at last,

And felt strange new joy as the worn head lay

Sweat of the forehead, dryness of the lips,

Washed utterly out by the dear waves o’ercast,

Do I not know now of a day in Spring?

No minute of that wild day ever slips

And wheresoever I may be, straightway

Thoughts of it all come up with most fresh sting:

And went without my ladies all alone,

In a quiet garden walled round every way;

That shut the flowers and trees up with the sky,

And trebled all the beauty: to the bone,

With weary thoughts, it pierced, and made me glad;

Exceedingly glad, and I knew verily,

I dared not think, as I was wont to do,

Sometimes, upon my beauty; If I had

And, looking on the tenderly darken’d fingers,

Thought that by rights one ought to see quite through,

Round by the edges; what should I have done,

If this had joined with yellow spotted singers,

But shouting, loosed out, see now! all my hair,

And trancedly stood watching the west wind run

I lose my head e’en now in doing this;

But shortly listen: In that garden fair

Wherewith we kissed in meeting that spring day,

When both our mouths went wandering in one way,

And aching sorely, met among the leaves;

Our hands being left behind strained far away.

Had Launcelot come before: and now, so nigh!

After that day why is it Guenevere grieves?

Whatever happened on through all those years,

God knows I speak truth, saying that you lie.

If this were true? A great queen such as I

Having sinn’d this way, straight her conscience sears;

Slaying and poisoning, certes never weeps:

Gauwaine be friends now, speak me lovingly.

All through your frame, and trembles in your mouth?

Remember in what grave your mother sleeps,

Men are forgetting as I speak to you;

By her head sever’d in that awful drouth

I pray your pity! let me not scream out

For ever after, when the shrill winds blow

For ever after in the winter night

When you ride out alone! in battle-rout

Ah! God of mercy, how he turns away!

So, ever must I dress me to the fight,

See me hew down your proofs: yea all men know

Even as you said how Mellyagraunce one day,

All good knights held it after, saw:

Yea, sirs, by cursed unknightly outrage; though

You, Gauwaine, held his word without a flaw,

This Mellyagraunce saw blood upon my bed:

Whose blood then pray you? is there any law

Lie on her coverlet? or will you say:

Your hands are white, lady, as when you wed,

I blush indeed, fair lord, only to rend

My sleeve up to my shoulder, where there lay

The honour of the Lady Guenevere?

Not so, fair lords, even if the world should end

Instead of God. Did you see Mellyagraunce

When Launcelot stood by him? what white fear

His side sink in? as my knight cried and said:

Slayer of unarm’d men, here is a chance!

Setter of traps, I pray you guard your head,

By God I am so glad to fight with you,

Stripper of ladies, that my hand feels lead

For all my wounds are moving in my breast,

And I am getting mad with waiting so.

Who fell down flat, and grovell’d at his feet,

And groan’d at being slain so young: At least,

At catching ladies, half-arm’d will I fight,

My left side all uncovered! then I weet,

Upon his knave’s face; not until just then

Did I quite hate him, as I saw my knight

With such a joyous smile, it made me sigh

From agony beneath my waist-chain, when

The fight began, and to me they drew nigh;

Ever Sir Launcelot kept him on the right,

And traversed warily, and ever high

Sudden threw up his sword to his left hand,

Caught it, and swung it; that was all the fight,

For it was hottest summer; and I know

I wonder’d how the fire, while I should stand,

Yards above my head; thus these matters went;

Which things were only warnings of the woe

For Mellyagraunce had fought against the Lord;

Therefore, my lords, take heed lest you be blent

Against me, being so beautiful; my eyes,

Wept all away to grey, may bring some sword

Like waves of purple sea, as here I stand;

And how my arms are moved in wonderful wise,

See through my long throat how the words go up

In ripples to my mouth; how in my hand

Of marvellously colour’d gold; yea now

This little wind is rising, look you up,

Within my moving tresses: will you dare,

When you have looked a little on my brow,

For any plausible lies of cunning woof,

When you can see my face with no lie there

But in your chamber Launcelot was found:

Is there a good knight then would stand aloof,

O true as steel come now and talk with me,

I love to see your step upon the ground

That gracious smile light up your face, and hear

Your wonderful words, that all mean verily

To me in everything, come here to-night,

Or else the hours will pass most dull and drear;

Get thinking over much of times gone by,

When I was young, and green hope was in sight:

And no man comes to sing me pleasant songs,

Nor any brings me the sweet flowers that lie

To see you, Launcelot; that we may be

Like children once again, free from all wrongs

Just for one night. Did he not come to me?

What thing could keep true Launcelot away

If I said, Come? there was one less than three

Till sudden I rose up, weak, pale, and sick,

Because a bawling broke our dream up, yea

For he looked helpless too, for a little while;

Then I remember how I tried to shriek,

The stones they threw up rattled o’er my head

And made me dizzier; till within a while

On Launcelot’s breast was being soothed away

From its white chattering, until Launcelot said:

Judge any way you will: what matters it?

You know quite well the story of that fray,

How Launcelot still’d their bawling, the mad fit

That caught up Gauwaine: all, all, verily,

But just that which would save me; these things flit.

Whatever may have happen’d these long years,

God knows I speak truth, saying that you lie!

She would not speak another word, but stood

Turn’d sideways; listening, like a man who hears

Of his foes’ lances. She lean’d eagerly,

And gave a slight spring sometimes, as she could

Her cheek grew crimson, as the headlong speed

Of the roan charger drew all men to see,

The knight who came was Launcelot at good need.